Ghislaine Boddington’s vision of the future is one where people talk interchangeably about their digital and physical selves, a world in which microchips embedded under your skin enable you to have a physical relationshipwith another person remotely.

“By the time the eight-year-olds of today turn 18, the microchip will be an 18th birthday present,” says Ms Boddington. “You can’t say that now about VR [virtual reality] headsets.”

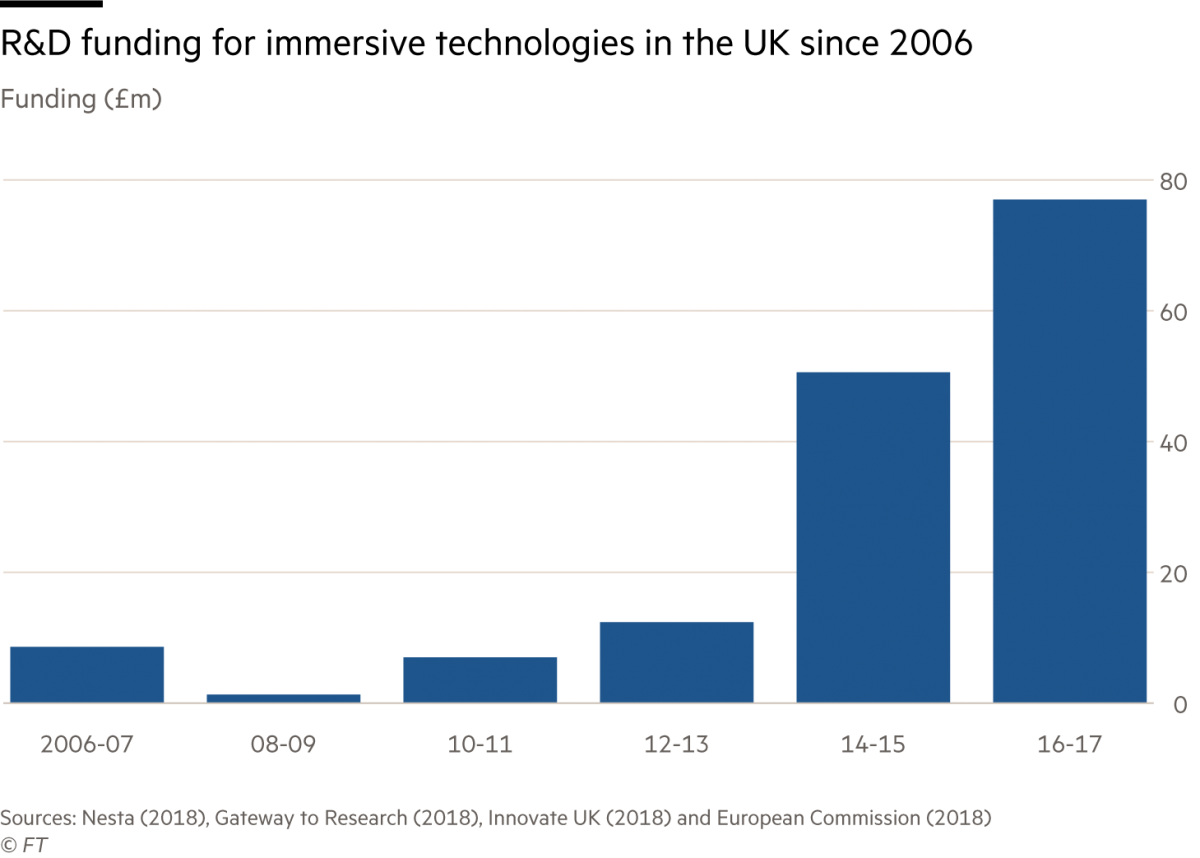

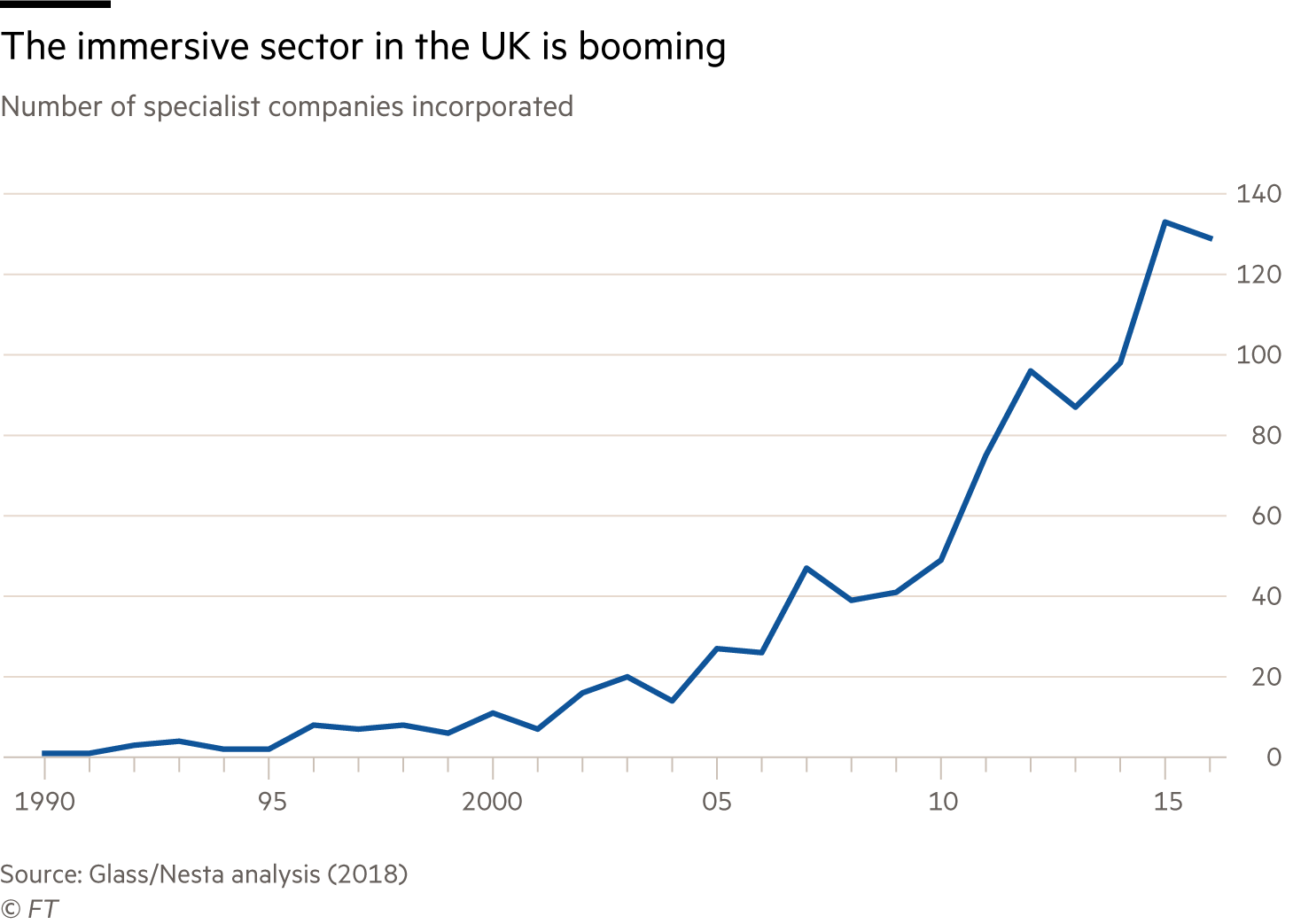

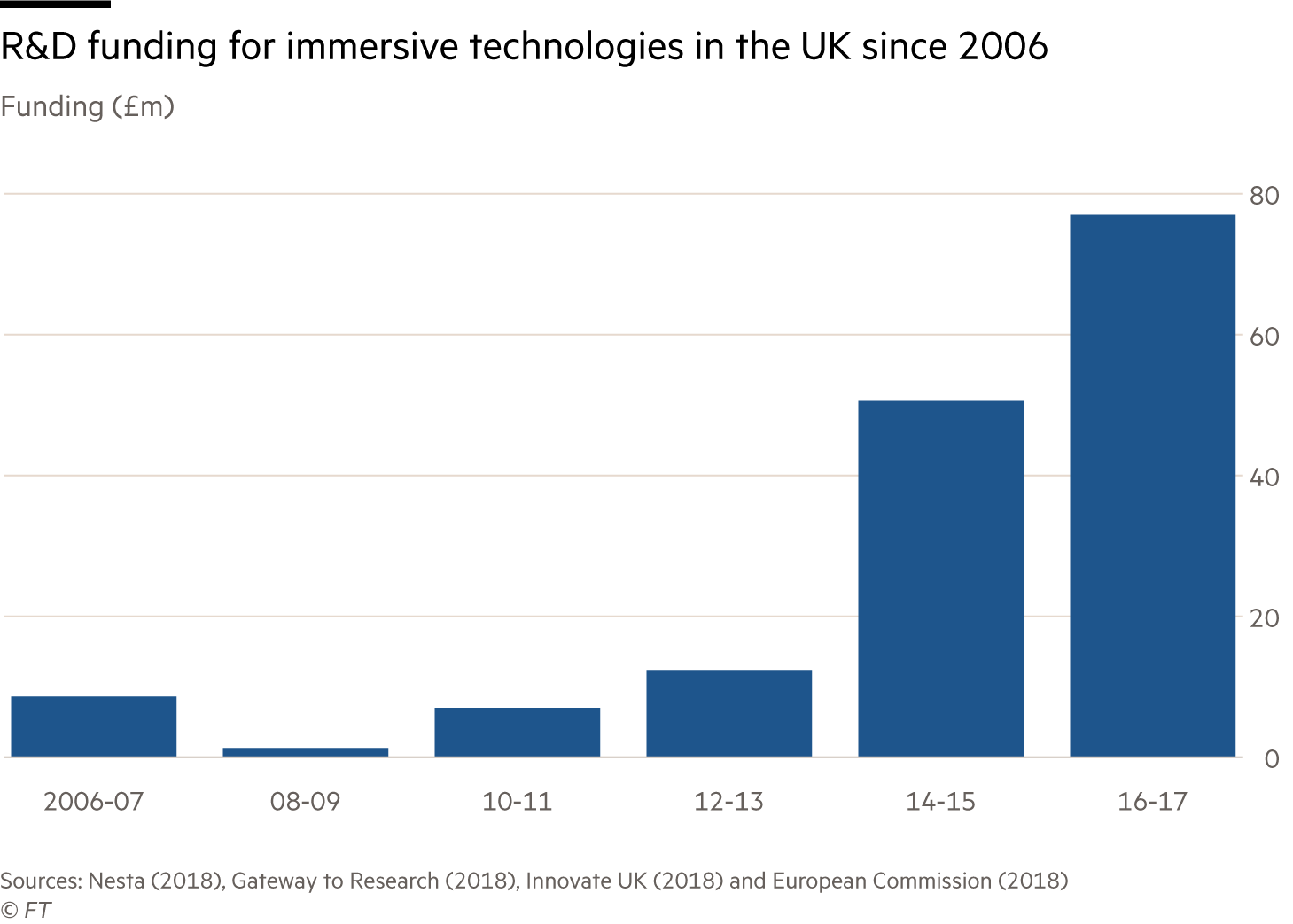

Ms Boddington is a pioneer in immersive technology, which emulates the physical environment through a digital or simulated world. The sector, which includes VR, augmented reality and mixed reality (which combines the first two), is projected to make the UK £1bn by the end of this year, according to the think-tank Nesta.

As co-founder and creative director of East London design collective called body>data>space, 56-year-old Ms Boddington focuses on blending the virtual and physical by combining telepresence — using tech to participate in distant events — virtual worlds and experimental environments that can be controlled using physical gestures. These include 210-degree domes or “spheres” — entertainment venues in which a VR immersive experience can become a shared social activity rather than a singular one experienced via a headset.

© Archive of body>data>space

In the 1990s, Ms Boddington, a trained dancer, became part of a movement called dance tech, where she experimented with telepresence, streaming and VR, long before they were adopted more widely.

Though she worked alongside many feminists during that time, Ms Boddington says she wore glasses between the ages of 25 and 35 in order to be taken more seriously by the men in her field. “I now wear contact lenses,” she says with a smile, “but it was probably the right decision then.”

Today, just 22 per cent of tech directors in the UK are women, according to a recent study by Tech Nation, a UK network for tech entrepreneurs. The perceived under-representation of women in VR and augmented reality in particular is coming under greater scrutiny, but collating accurate data on this sector is difficult, says George Windsor, head of insights at Tech Nation.

Ms Boddington has recently become involved in the launch of a start-up accelerator — sponsored by Deutsche Bank — which supports women-led social technology businesses through investment and mentoring programmes. She says the overwhelming majority of VR companies she encounters through her work are run by men.

This can create problems. So far, the use of VR technology has gained limited traction among women. Two-thirds say they are unlikely to try either VR or AR, according to a 2017 report by the consultancy EY, compared with half of men. “Like so many technologies, adoption happens when consumers don’t think about the technology itself but what it allows them to do,” says Martyn Whistler, an analyst at EY. Developing real-use applications in areas such as retail, tourism and fitness will demonstrate their value to women, he adds.

Ms Boddington agrees. “A high proportion of VR content is male heterosexual porn,” she explains. “Content creators need to think in a much more diverse way” to broaden the technology’s appeal, she adds.

She prefers to focus on the body from a different perspective. She uses the phrase “internet of bodies” to encompass the idea that the body should be central to the digital experience.

© Archive of body>data>space

Too often, Ms Boddington says, creative companies will try to retrofit their products to cater for women.

“I make sure from the beginning of your company idea or project, you have women [involved], diversity of culture, and somebody from the body-knowledge side such as a dancer, physio, biologist or neurologist,” she says. “You can’t, as three lads, make a VR piece or a piece of immersion work and then, six weeks in, bring in a user testing group and then find out women don’t like that very much.”

China is at the forefront of immersive tech implementation and dome-building. The immersive shared venues are being used in education, training and entertainment. “A restaurant in Shanghai, for example [can be] half full each night of physical diners from Shanghai and half full of diners from Beijing,” she says. Telepresence or holograms, meanwhile, allow “families who live in different countries to have dinner together virtually”, she explains. “You can even physically feel each other through touch-feel sensors.”

Immersive tech inevitably has implications for physical intimacy. “You can be more physically in touch with your partner when they are travelling abroad — from a heartbeat sensor called Pillow Talk, to using implants [or] silicone-based gels in your erogenous zones for sexual intimacy when you are apart,” she says.

Ultimately, broadening the appeal of VR is dependent on achieving gender equality in the industry, Ms Boddington believes. “We won’t innovate unless we have a diverse group involved — whether it’s a new product or making a new experience,” she says.