Mainstream brands have been slow to embrace adaptive design, but Tommy Hilfiger has stood apart and has proof it’s working. Now LVMH has signalled an interest in the burgeoning market.

When Tommy Hilfiger first designed an adaptive fashion line in 2016, he was an outlier in a space otherwise dominated by hyper-functional, medical garments catered to the elderly. Five years later, the adaptive market remains largely untapped by mainstream fashion brands, but Tommy Hilfiger is furthering commitments after commercial success.

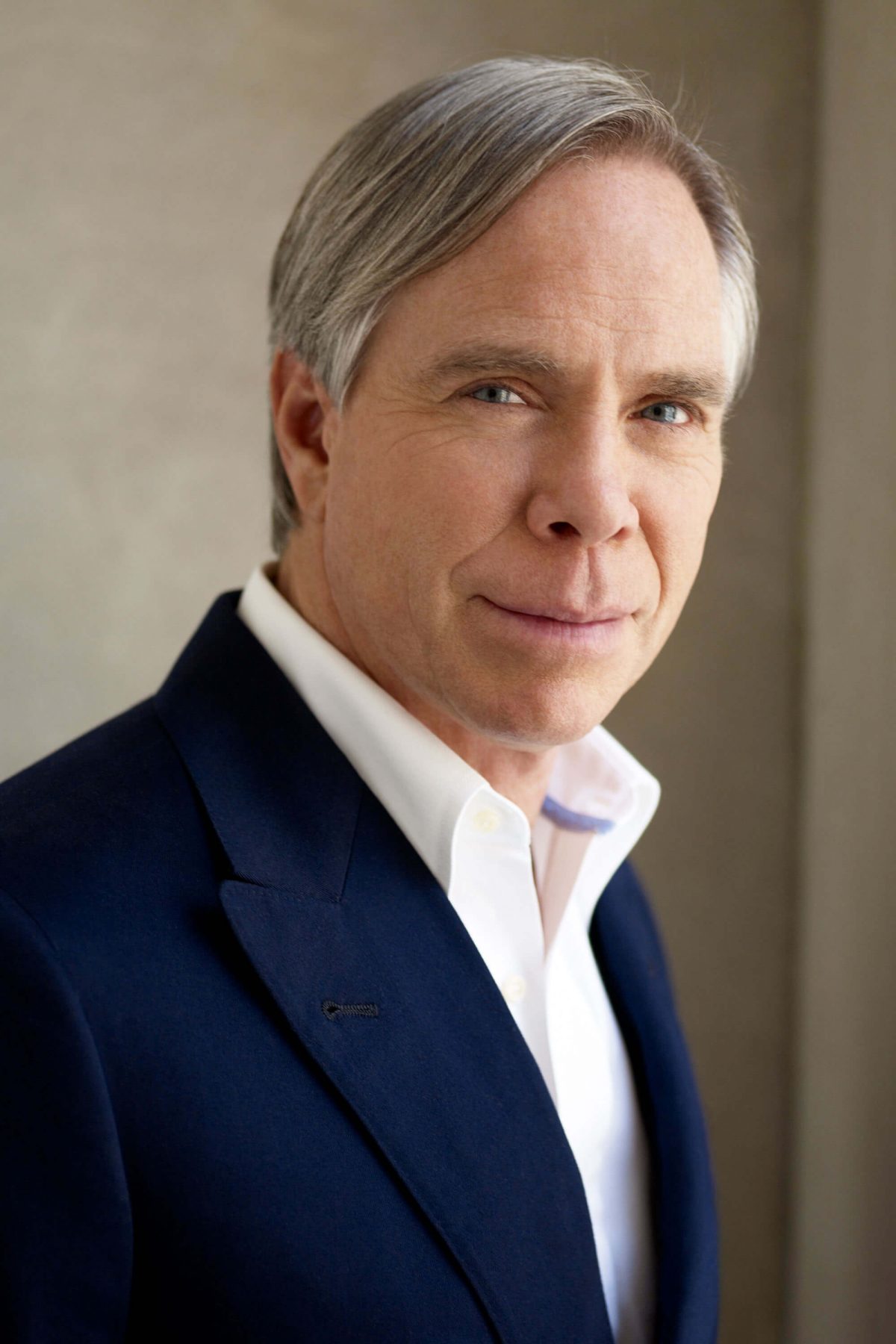

Tommy Hilfiger will increase its Tommy Adaptive collections to two per year and expand availability worldwide, having already added Europe, Australia and Japan last year. Seventy-five per cent of consumers who buy the range are new to Tommy.com, typically shop non-adaptive sections and those that do spend 4.8 times more than the average customer, according to the brand. “Leading the way for adaptive fashion is something we’re very proud of,” Hilfiger wrote via email to Vogue Business, adding that his passion for adaptive design stems from the issues his autistic children have faced getting dressed.

Adaptive design, which tweaks existing clothing design to be more inclusive to people with disabilities, has a potential market value of $64.3 billion, according to Coresight Research. Mass brands including Target, Land’s End and Kohl’s, as well as multi-brand marketplaces such as Global Brand Group’s Juniper Unlimited and Australian newcomer Every Human, have led the category. Luxury brands have largely overlooked the space, but that’s starting to change.

American designer Christian Siriano is working on an adaptive line with the actress Selma Blair, who was recently diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Inclusive fashion nonprofit Runway of Dreams is contributing to educational programming across LVMH, where Marc Jacobs runs additional inclusive design workshops for staff. No LVMH brands sell adaptive clothing as yet, but it’s on the company’s radar. “In the months and years ahead, we’ll continue to work towards a future of greater equity, inclusion and opportunity in our organisation and our industry,” says Gena Smith, senior vice president of human resources and head of global executive and creative recruitment for LVMH.

Some of the Tommy Adaptive features: magnetic button closures, velcro openings and internal toggles.

According to Coresight, 12.7 per cent of Americans have a disability, and US consumers will spend $1.3 billion on adaptive designs in 2021. As more brands enter the space, experts expect competition and employment opportunities for people with disabilities to increase. “Adaptive design is one of the few segments where demand and opportunity are there, but the market isn’t,” says Erin Schmidt, beauty industry analyst at global retail advisory Coresight Research. “There are still a lot of misconceptions about [this consumer’s] ability or willingness to spend. I would encourage brands and retailers to educate themselves and find the opportunities.”

Understanding needs

For fashion brands, education is paramount to entering the adaptive design space.

When fashion enthusiast Quin Lewis became an amputee 15 years ago, his seamstress mother would personally “hack” or adapt his clothes. “I often have the right leg of my trousers shortened because of my prosthetic, and I need an extra couple of inches around my waist for the bucket strap my residual limb sits in,” explains Lewis. “The bucket is very rigid, and it often wears down fabric when I’m sitting — I get holes in my pants after two hours at brunch. It would be helpful if designers included extra fabric for internal patches, similar to how they include extra buttons.” He would like to see made-to-order and customizable options for adaptive clothing.

RICHARD PHIBBS/TOMMY HILFIGER

Many brands approach adaptive clothing by re-educating designers. Hilfiger says his team was able to draw on its athletic wear experience, which has a similar focus on movement, performance and functionality, to create its collection. Sarah Horton, senior director of innovation and integrated marketing at Tommy Hilfiger, says one of the biggest challenges has been communicating how its Adaptive line supports various dressing challenges. Consumers can filter Adaptive products by solution (easy closures, ease of movement, seated wear) or feature (easy open necklines, magnetic buttons, hook and loop closures, internal pull-up hoops, low front and high back, part openings, and side seam openings).

New York brand Ffora creates adaptive accessories for wheelchair users, including bags and cup holders.

Adaptive design doesn’t just apply to products, but the experience of buying them. In the US, Tommy Hilfiger’s e-commerce site now uses fonts, colours and layouts designed to be inclusive to a range of visual, auditory and cognitive experiences. Adaptive products and features are illustrated with animations and videos, all accessible through guided shopping journeys and voice navigation powered by Amazon Alexa. Support staff are available around the clock and Adaptive shoppers also benefit from free shipping, which uses pre-glued, resealable bags that are easier to open than the traditional cardboard box.

In-store, this could mean wheelchair-accessible changing rooms, disability representation among mannequins, sensitivity training for retail staff and seated-height registers.

Physical retail has been slower to change at Tommy Hilfiger, but the brand has committed to making all of its retail stores and showrooms inclusive to all shoppers by 2023, according to Tommy Hilfiger. “We know there’s a lot more we can do to create a more inclusive in-store shopping experience,” he says. “We want to do it right, so we’re spending time with our differently abled consumers to learn more about the challenges they face so we can make meaningful and impactful improvements where they’re needed most.”

Collaboration and consumer feedback are key to inclusive products

Hilfiger is not the only adaptive fashion pioneer whose interest was piqued by a personal experience of disability. Maura Horton founded Magna Ready when her husband was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, Toronto designer Izzy Camilleri started IZ Adaptive after the late quadriplegic journalist Barbara Turnbull commissioned her to make a bespoke wheelchair-friendly cape, and occupational therapist Joseph DiFrancisco created Friendly Shoes after watching his patients struggle with inaccessible shoes.

These startups are in a prime position to collaborate with luxury brands that are new to adaptive design, helping them avoid risks and missteps where stakes are high. Adaptive clothes that don’t centre the needs of the wearer can cause injury or even be lethal, says Camilleri.

Izzy Camilleri’s Game Changer Pant, which combines the look of denim jeans with the comfort of a seamless back. The pants are designed to avoid pressure sores among seated wearers.

DAVID KERR, CHIARA DE FALCO

Brands can also partner with fashion students to accelerate change. Juniper Unlimited launched a postgraduate project with IFA Paris this year, which will see two winning students (to be announced in April) sell their adaptive, sustainable products on the site.

Welsh designer Lucy Jones founded Ffora in 2017 after a Parsons project encouraged her to challenge her own biases as a designer. Her modular wheelchair-attachable accessories won the CFDA’s Elaine Gold Launch Pad programme in 2018, and she is now collaborating with wheelchair manufacturers on new functions. “Ffora has so much data on adaptive design, we would love to collaborate with luxury brands to take it to the next level. Nobody has to start from zero.”

Many adaptive brands host regular focus groups, actively listening to feedback from people with disabilities and using that to drive their innovations. “Reach out and listen to your audience,” says Hilfiger. “It’s their needs you’re trying to meet, and without them you’ll never get it right.”

Hilfiger may be an outlier for now, but there’s ample opportunity ahead. “Every single category of clothing can be improved,” says Camilleri. “It just takes a fresh pair of eyes.”