The galleries are shut, the museums are closed. But worry not, art fans. We’ve tapped some of the art world’s leading curators, collectors and experts to talk us through the exhibitions none of us can attend in person. Here Gregor Muir, the director of Tate’s International Collection, and Fiontán Moran, assistant curator at Tate Modern, talk us through the gallery’s blockbuster Andy Warhol show.

To date, a great many Andy Warhol exhibitions have taken a familiar path, with Pop Art representing the bulk of the artist’s career. However, Warhol’s influence extends far beyond the Sixties, with Pop Art accounting for only three years of his production. In fact, it’s the period after the Sixties that often contributes to our understanding of Warhol as an artist who champions new forms of celebrity, and business art, while investing himself in new areas of popular culture, to include music, magazines and TV.

In contrast to received notions, we wanted to locate the artist in a humanistic setting. Who was Warhol? Where did he come from, and how did his lived experience inform his work? We wanted to strip away the hype and the myth, often put out by Warhol himself as a means of shrouding his true identity. We wanted to look at Warhol for who he was, taking into account his family’s journey to America from Eastern Europe, his queer identity, and the way in which his work would ultimately be informed by death and religion. With this in mind, we wanted to look at Warhol afresh. Here are some of our exhibition highlights.

Charles Lisanby

Throughout the Fiftes, Warhol exhibited his drawings in various New York venues, including a set grouped around the title Studies for a Boy Book. While the publication was never produced and we don’t know exactly which drawings were included, this portrait of the production designer Charles Lisanby is a perfect example of the intimate way Warhol approached art making and his elegant drawing style. Lisanby was one of Warhol’s first crushes, who he tried to charm by buying a stuffed peacock that they had both admired on their first walk home together.

Round Marilyn

Marilyn Diptych is one of the most popular works in the Tate Collection, so we were very excited to be able to show this alongside the other diptych, Marilyn Monroe’s Lips (on loan from the Hirshhorn Museum) as well this work, Round Marilyn, on loan from Museum Brandhorst. All three works were created in 1962, the year that Monroe died, and have been interpreted as a contemplation on the life of the actor, who at the time was one of the most famous women in the world. The tondo is particularly interesting for the way it turns the image of Marilyn into a modern-day saint. By placing her image against a gold background, Warhol appears to have been referencing the tradition of Byzantine icon painting, which he would have known from museums and his own religious upbringing.

Sleep (1963)

For most of the Sixties, Warhol dedicated his time to filmmaking, which was being used by many artists in new and exciting ways. Sleep was his first major work in the medium, and opens our exhibition. The silent five-hour film consists of a series of short clips, edited together, that document the poet John Giorno – who was briefly Warhol’s lover – sleeping. Warhol was fascinated by the ability of his friends to stay up for days on end while using drugs and wondered whether sleep would soon become obsolete. Featuring no dramatic narrative, Warhol created a film that could be contemplated like an abstract painting. In 2004, Sam Taylor-Johnson made her own version of the film when she filmed David Beckham sleeping.

Screen Tests

Alongside his more experimental movies, from 1964 to 1966 Warhol created short film portraits that came to be known as the ‘Screen Tests’. The set up was simple. A person was asked to look directly at the camera for the three-minute duration of the film reel, ideally without moving or blinking. As the camera was often left running with no one behind it, the works became a test of the subject’s patience. Once projected, they become a test for the viewer too. The series documents a number of Warhol’s so-called ‘superstars’, such as Edie Sedgwick and the drag queen Mario Montez, but also other notable figures who passed through the Factory including Allen Ginsberg, Susan Sontag and Bob Dylan.

Silver Clouds

In 1965, at the height of his fame as an artist, Warhol announced his retirement from painting in favour of filmmaking. He staged his farewell with an installation in a New York gallery the following year. One room consisted of nothing but wallpaper featuring a fluorescent pink cow. In the other, metallic silver balloons filled with helium floated through the gallery space and could be interacted with by the viewer. Titled Silver Clouds, Warhol described them as ‘paintings that float’, but they can also be seen to queer conventional thinking about sculpture, specifically the dominance of minimalist art in the New York scene at the time. This was an art based on order, mathematical precision and industrial materials. Instead, Warhol’s installation emphasised fluidity, movement and participation.

Vacuum Cleaning

In 1972, Warhol was asked, along with a number of other artists, to create works for the exhibition ‘Art in Process’ at the Finch College Museum of Art, New York. Warhol’s response was to purchase a vacuum cleaner, which he used to clean the carpet in the gallery. The gallery displayed the signed dust bag and vacuum on a plinth along with photographs documenting the process. It’s a fantastic example of Warhol’s interest in performance and the everyday actions that we take for granted.

Ladies and Gentlemen (Marsha P. Johnson)

A room of the exhibition is dedicated to Warhol’s ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’ paintings, which is one of his biggest series, yet little known. It depicts Black and Latinx drag queens and trans women who were chosen from bars in New York. The series showcases Warhol’s painting technique in the Seventies, where he would use expressive brushmarks and even use his fingers to animate the dynamic poses of the models, and then screenprint their photograph on top.

While the original commission asked that the identities of the sitters be anonymous, in recent years there has been more interest in the series as a portrait of a community that was rarely depicted in painting. One of models was Marsha P Johnson, who was at the Stonewall uprising of 1969 that ushered in the gay and trans rights movements. Johnson was a remarkable figure who was a fixture of the West Village scene, performed in drag shows, and set up a home for homeless LGBTQ+ youth, so it’s special to be able to foreground her in the exhibition.

Oxidation Painting (1978)

The ‘Oxidation’ series of paintings was created by Warhol and his assistant Ronnie Cutrone either pissing or pouring urine onto a canvas primed with copper-based paint. The chemical reaction, or oxidation, created ‘blooms’ of colour. Warhol was especially excited by the change of colour that was created as a result of his Cutrone’s vitamin B supplements. The works have been interpreted as a parody of abstract expressionist painting and are an important example of Warhol’s collaborative, playful and experimental approach to painting.

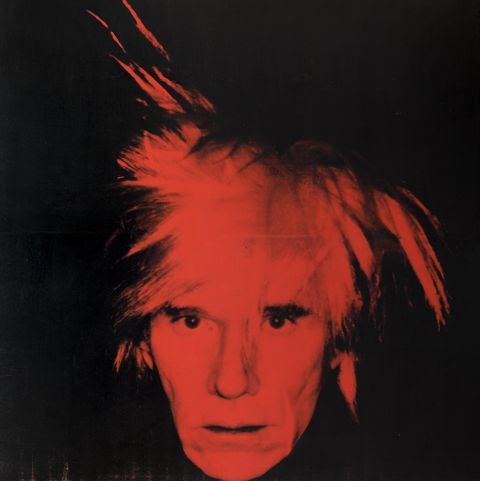

Wigs / fright wig Self-Portrait

Despite his desire for fame, Warhol was incredibly insecure about his appearance. He started wearing a wig in the late Fifties to cover up his premature balding, which came to be an integral part of his carefully created persona. In the exhibition we have three of Warhol’s own wigs from the Eighties, borrowed from the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. By this point his wigs had become more exaggerated, which culminated in his so-called ‘fright wig’ self-portraits of 1986, which were first exhibited in London and show his head floating against a dark backdrop.

Sixty Last Suppers (1986)

The final work in our exhibition is ‘Sixty Last Suppers’, which depicts a late copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Last Supper’ mural, screen-printed sixty times across a ten-metre long canvas. It’s a moving and dramatic work that references his religious upbringing and plays on the authenticity of the original mural. It was also created at a time when Warhol was increasingly surrounded by death as the AIDS epidemic swept through New York and took the lives of many of his friends, including his former partner, Jon Gould. While Warhol was not a queer activist, ‘Sixty Last Suppers’ could be seen as a moving portrayal of endless loss, reminiscent of the wall graves found in many cemeteries. ‘Sixty Last Suppers’ would turn out to be one of Warhol’s final works. Soon after the first exhibition of the series in Milan, he had surgery on his gallbladder and died shortly after, at the age of 58.

Tate Modern is currently closed until further notice – please check www.tate.org.uk for more updates. In the meantime audiences can enjoy Tate’s enhanced digital offer which includes a filmed tour of Andy Warhol on Tate’s YouTube channel and website, as well further exhibition-related content, ranging from a first person take on the artist from his close friend Bob Colacello, to a video tutorial on how to screen-print like Warhol.