Fashionably late

Sew-long to fairness. Source: Picture Alliance

Sew-long to fairness. Source: Picture Alliance

When a factory collapse in Bangladesh claimed the lives of hundreds of textile workers in 2013, German retailers were quick to express the need to improve working conditions in Asian sweatshops. But five years on it seems they’re much less keen to actually do anything about it.

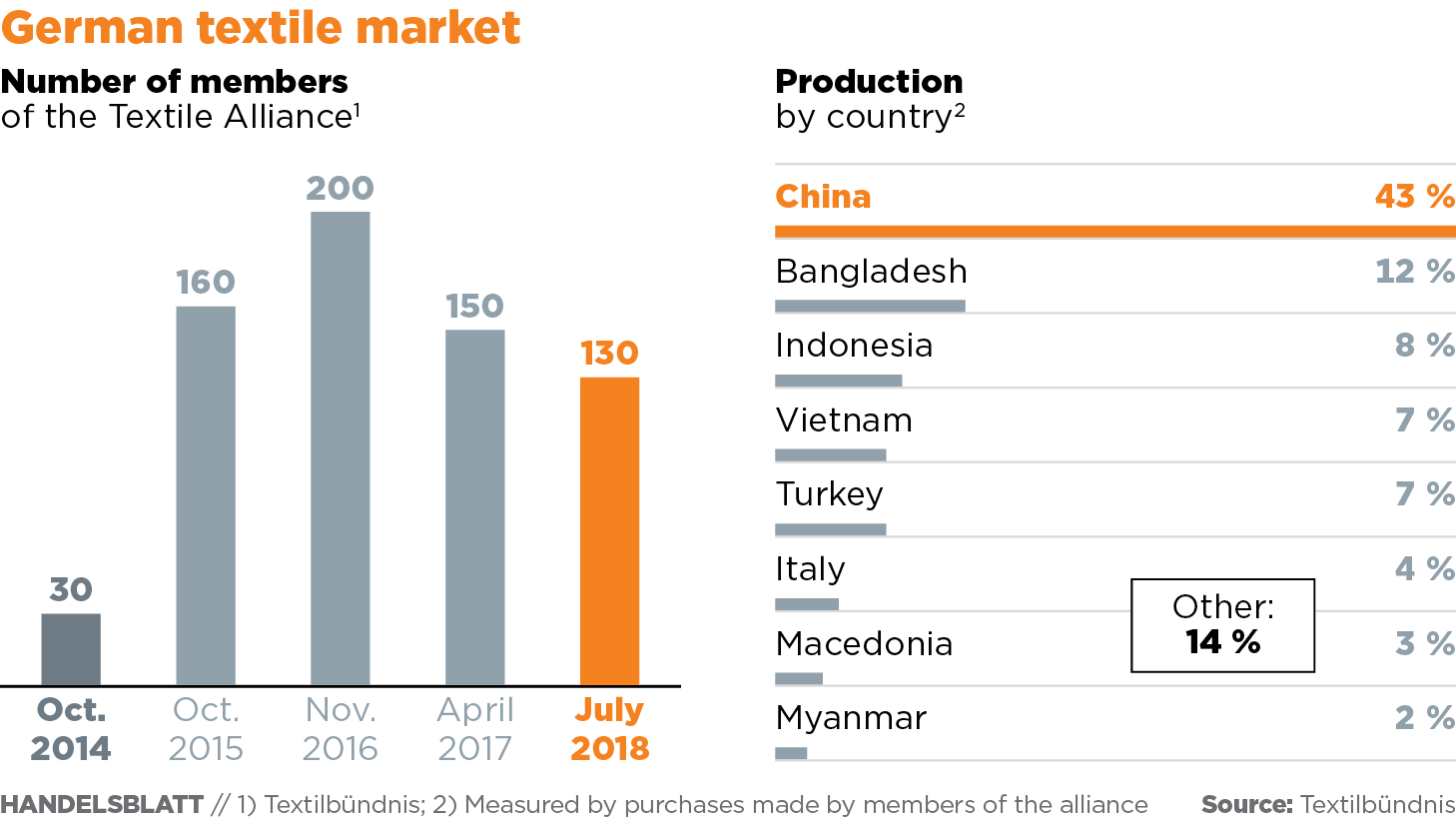

An alliance of retailers formed in 2014 with the aim of tackling the problem is crumbling fast. In 2016, there were nearly 200 members; now it is 130. This year alone, 25 retailers either quit or were thrown out for not honoring their commitments to report on improvements made in their supply chain.

There’s a simple reason why companies are jumping ship. Talk is cheap, and the alliance is now trying to move from words to action.

Previously, members showed to what extent they met their goals in the previous year and formulated new ones. Now, they are expected to publish these so-called roadmaps in August, opening them to independent auditors who will scrutinize the submitted documents and ask tough questions. For the first time, the retailers will be measured by their achievements.

But now the alliance’s management team would consider it a success if just 30 companies published their plans.

The scheme was launched by then Development Minister Gerd Müller, who wanted the grouping to cover 75 percent of the entire German textile market by the end of 2018. But that goal is far out of reach with the percentage currently at 49 percent.

Crucially, big names in German retail are missing. All the major department store chains such as Kaufhof, Karstadt, Breuninger, Wöhrl and Ludwig Beck are conspicuous in their absence. Ernsting’s Family, a major player, recently quit and the large chain Peek & Cloppenburg never even joined.

Online retailer Zalando, which has been criticized for refusing to join, said it is focusing on an international rather than a German sustainability alliance because it has an internationalreach. Its own brand unit zLabels joined the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) which in turn cooperates with the textile alliance.

“Now the wheat is separating from the chaff,” said Ansgar Lohmann, head of sustainability at discount retailer Kik. “Unfortunately, many companies don’t appreciate the added value that membership of the textile alliance offers them, they only see the added work.”

Kik was once the focus of criticism in 2013 after the collapse of the eight-floor Rana Plaza building in Dhaka, Bangladesh, in which more than 1,000 people died. The company, which was among firms that had clothes made in the factory, responded by getting heavily involved in improving factory conditions.

An unrealistic alliance?

The problem isn’t just a lack of commitment by German retailers, but that many companies are struggling to meet the alliance’s requirements.

“It’s clearly harder for small and mid-sized companies to meet the financial and staffing challenges entailed in taking part in the textile alliance,” said Nanda Bergstein, head of corporate responsibility at retailer Tchibo. “But big companies have to cope with greater complexity. It’s often not easy to agree on a common denominator.”

Retailer P&C’s argumentation is that it sells a high proportion of third-party brands and would struggle to meet the requirements because many of its suppliers hadn’t joined. But that’s a problem shared by many retailers that have joined.

Understandably, human rights groups are losing patience. “The textile alliance is at risk of remaining ineffective if its own targets aren’t met,” said Berndt Hinzmann, of development network INKOTA.

The alliance’s focus this year has been on providing living wages. But not much has happened in that regard, he said.

Florian Kolf leads a team of correspondents, who cover the trading and consumer sector for Handelsblatt. Georg Weishaupt covers the luxury and fashion industry for Handelsblatt. To contact the authors: kolf@handelsblatt.com and weishaupt@handelsblatt.com

Make sure to sign up for our free newsletters too!