Since taking the reins as chief executive of Kindred at the beginning of the year, Jim Liefer has been focused on commercializing his company’s autonomous robots. But unlike forward-projecting use-cases for robots that may (or may not) one day take over for human beings in a wide swath of functions, Kindred’s current robots are purpose-built for the floor of retail fulfillment centers. That puts Kindred in the middle of an interesting business question: Given rising consumer expectations associated with online ordering, can anyone match or beat Amazon when it comes to speed, accuracy and efficiency?

With a background in operations at Walmart and One Kings Lane, Liefer asserts that his company’s core IP represents a significant advancement in retail operations. That’s because while industrial robots have worked well on manufacturing floors, robots have historically underperformed in e-commerce fulfillment centers, which require systems to handle objects of various shapes and sizes. Kindred’s approach is also notable because of its low-risk model that doesn’t require customers to make major capital investments. Instead of paying for the robot hardware, clients such as Gap pay based on the robots being able to successfully pick and sort items in a warehouse.

In the interview below, Liefer was eager to elaborate on his company’s core product, SORT. He was also happy to address the labor and throughput challenges facing Kindred’s clients as they look to thrive this holiday season. Finally, he offered his candid perspective on the ongoing debate over AI and jobs.

Gregg Schoenberg: Jim, it’s good to see you. I was interested in talking with you because Kindred is focused on the unsexy, but very important part of robot and AI technology that deals with e-commerce and gives insight into how our economy is changing. And by unsexy, I mean that your robots don’t do parkour.

Jim Liefer: Thanks, Gregg. I’ll start out by saying that sexy is in the eye of the beholder. If you came from retail operations companies like Walmart, sexy would be not having to re-engineer or re-architect my building every year to handle the next peak.

GS: Fair enough. So where has that “sexy” journey taken the company today?

JL: We’ve evolved from a research and engineering company into a customer-focused organization. Today, there are four primary components that Kindred is working on: vision capability, grasping/manipulation capability, ability to identify what’s being held onto and then placing an item somewhere.

GS: And today, your solution is being applied to retail fulfillment centers?

JL: Yes, in retail fulfillment distribution centers, but not the consumer-facing side of retail. Still, there is a tremendous amount of automation in these centers. There are sorters and power conveyance, and there are forklifts running around. But we saw gaps in those in-between moments, the need to take individual pieces from automation A to automation B. That’s where Kindred now can fill those gaps, and it’s a big market.

GS: Do you make robots or do you make cobots?

JL: We’re absolutely collaborating with the humans, but we’re not letting them get that close to the robot. We’re letting the humans do what they do best, like higher-level thinking and dealing with more ambiguity than the robot can handle.

GS: But your solution is designed with the intent that there are going to be people that interact with it?

JL: For some period of time to come, I believe that is going to be true. That’s the design of what we have now. The reason I say it that way is that even today, the aspects of how product arrives at our solution varies, and some day, there might be another mobile robot that serves our robot, that brings the product to us.

Product

GS: At the core of the solution is your autograsp technology, right?

JL: The autonomous grasp algorithm is the core of our AI technology, which is combined with vision and grasping capabilities.

GS: I’m guessing that even though that grasp technology looks simple, it’s actually a big feat of both software and hardware innovation.

JL: Yes, absolutely. The grasping technology is a combination of AI that can understand the ambiguity that it’s dealing with. But there’s also the the physical side of it. Not only do you have to be able to get to a grasp-point, but you also have to grip it correctly.

Some day, there might be another mobile robot that serves our robot, that brings the product to us.

GS: What’s the inherent challenge with getting the gripping correct?

JL: It needs to be precise enough to pick up the item you want. It also has to have enough torque to be able to hold onto the item when you’re moving it.

GS: Why is that so critical?

JL: Because you have to move at a speed that’s equivalent to a human or better in order to not lose it.

GS: What’s the installation process associated with putting a system into a facility?

JL: We literally roll them off the truck, roll them into place, plug them into 110 power and a data port, and maybe do some final provisioning of software. All in, it takes us anywhere from five to eight hours to set up a robot. So it’s definitely plug and play.

Business Model

GS: I know you don’t actually sell the solution to a customer. Can you walk me through your model?

JL: In the days when I was in a Walmart facility and I wanted to implement a new solution, I would go out to a service provider and they would tell me how many millions of dollars to plunk down. I would pay for it and then someone would come in and build it, and then they would go away and I would try to operate it.

GS: How antiquated.

JL: In our world today, they tell us their throughput need and how many products they are trying to serve with robots. We then deploy the number of robots to the customer. We have an agreement that says you need 10 robots or whatever the number is, and we deploy robots that will serve X amount of products.

GS: How does the money flow work?

JL: It’s a robots-as-a-service model, where every time we successfully grasp and stow a product or item, they pay us something.

It takes us anywhere from five to eight hours to set up a robot. So it’s definitely plug and play.

GS: A commission of sorts.

JL A commission, right. So it’s not a purchase and walk away. And there are several reasons why we think that’s compelling for the customer. One, because it’s not a capital expenditure play for them; it doesn’t have to be multiple weeks, months or even years to get onto the capital budget. It’s an operating expense play.

GS: That sounds like a key consideration.

JL: Think of it this way. When an operating expense comes into play, in many cases, a director-level person of a fulfillment center can make the choice: Am I going to hire a human to do the job, or I can hire a robot to do that job? The other is that because we’re providing a service to the customer, we’re right there alongside them. It’s not as though we gave them something and said figure it out.

GS: Aren’t you making it very easy for clients to keep the robots around? Because it’s not costing them to have the robots sit on the fulfillment center floor.

JL: Well, okay, good question. In our model, we still have a minimum for the customer, because we’re paying down the robot. We don’t want to have a robot sitting there idle.

GS: In that case, what’s the break-even on how long the robot needs to be on site with the client?

JL: It’s somewhere between a year and a year and half to get the payback to cover the cost of building the robot.

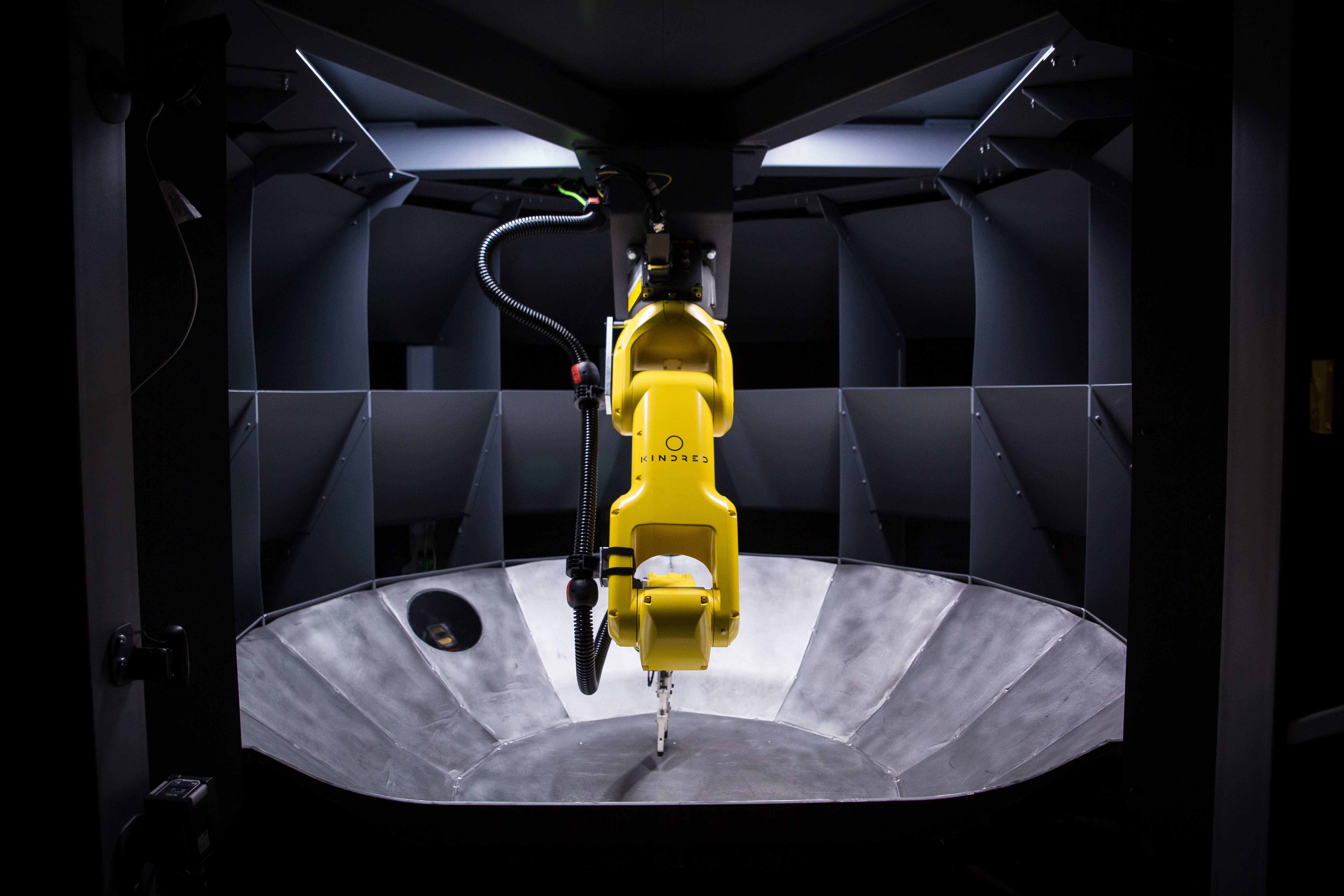

The Kindred.AI sorting robot in the lab.

GS: Does the counterparty risk become a factor? Because these machines are obviously expensive.

JL: Yes, that comes into play. At the same time, the robots themselves are quite… I want to say the word mobile. It’s relatively low-pain for us to roll them out and roll them to another customer facility that’s probably nearby. Of course, we don’t want to do that, but it’s possible to do it.

Amazon

GS: Of course not. But you’ve spent many years at Walmart, and you’re obviously very aware of the existential threat that Amazon poses to just about everybody that isn’t Amazon. Does Kindred aspire to help others thrive in a retail economy that is increasingly dominated by Amazon?

JL: Yes. It levels the playing field, because if our customer, the retailer, is able to have better throughput, get the products into the hands of the customer faster, then they have the ability to hold onto their customers. If they don’t do it, then those customers are going to go somewhere else.

Am I going to hire a human to do the job, or I can hire a robot to do that job?

GS: Looking to the future, do you want to go deeper within the apparel channel, or do you see other retail applications for your grasping technology?

JL: To recap, we figured out a very difficult problem, which is how to handle clothing in a polybag with a label on it. What seems like the most logical and reasonable place to go is to smaller items and maybe toy items or jewelry.

GS: But it has to be in a bag?

JL: It doesn’t have to be in a bag. In testing, we can pick up a pen or a pencil. We can pick up an iPhone and even general merchandise-related items like baby wipes or rubber balls.

Technology

GS: Let’s dive into your technology a little deeper. Is your tech based on reinforcement learning or deep reinforcement learning?

JL: Actually, both. The way that we’re operating the current SORT robot is that there are multiple AI algorithms that are running in concert together. So there’s the autonomous grasp algorithm, there’s a grasp verification algorithm, there’s a stow algorithm; there are multiple algorithms that are running to maintain that speed and accuracy. Then, there’s our team in the Toronto office—

GS: —That’s the team working on deploying more reinforcement learning?

JL: Yes, the reinforcement learning which would replace some of the deep learning algorithms that we have in place today.

GS: I read up on Rich Sutton, who, based on my research, is a big deal in reinforcement learning—

JL: —Yes. He’s a big deal and is a mentor to several of our people.

It’s relatively low-pain for us to roll them out and roll them to another customer facility that’s probably nearby.

GS: Sutton describes reinforcement learning as a learning system that wants something. Can you describe in lay terms how this is central to Kindred’s technology and how it is different than deep Learning?

JL: Here’s how I think of reinforcement learning versus deep Learning. Reinforcement learning is allowing the algorithm to determine all of the possible outcomes and all of the possible permutations. Think about something in a space where you want you to go from point A to point B. In reinforcement learning, that robot will achieve the goal by doing something called body babbling, which looks like it’s jittering around, looking at all the different possible solutions.

GS: So it takes longer to train a reinforcement algo?

JL: Yes, because in deep Learning, you are going to give it some sort of structure within parameters, because you sort of know what you want it to do. Then you look at body babbling, which is a much cleaner solution because the algorithm knows how to deal with all these variables because it’s explored every permutation.

GS: I saw that Kindred released a research paper last month. My top-line takeaway is that while reinforcement learning has made progress, it’s tough to train robots.

JL: I view it this way: In the last two years that I’ve been here at Kindred, I’ve seen things on a daily basis that I didn’t think were possible the week before or the month before. That’s a blanket statement, though, which is one of the reasons why I think people are anxious about AI and automation.

AI Anxiety

GS: So let’s talk about AI anxiety. Yesterday, I was on Bush Street and I watched this Cafe X robot serve coffee. Meanwhile, across the street, you’ve got this Blue Bottle that’s teeming with people, keeping its staff quite busy. Is that the future you see? Where workers are in demand, even in an era of well functioning robots that can grasp stuff?

JL: I think back to Tower Records in San Francisco in the 90s. It used to be packed. I mean, that’s where I spent every weekend. You never thought that would end, perhaps like some people at the Blue Bottle today. But there’s that flip point.

GS: I appreciate that honest comment.

JL: To me, I just think it’s inevitable, and I don’t think it’s bad. But I believe that we will embrace it, just as we embrace technology in our phones, because it will improve our lives in many ways and it will also make our lives more complicated.

GS: We’ve discussed previously, too, this idea that in the fulfillment centers where the Kindred robots are operating, there’s a labor shortage.

JL: Yes, there’s no employee there to do the job.

We can pick up an iPhone and even general merchandise-related items like baby wipes or rubber balls.

GS: And that’s because fulfillment centers are in locations that are often—

JL: —They’re clustered. They’re fighting for the same resources. Big Amazon has come in, they’re paying those workers more, so they’re siphoning all those workers away.

GS: What about temporary workers around the holidays?

JL: We said earlier that the robots are collaborative, working alongside and collaborating with the humans. Absolutely, there are places for the temporary workers to come in, and I want those humans to be fulfilled. In terms of helping our customer, it’s so painful to get even a temporary worker, give them a job that’s very mundane, have them leave and then have to hire another temporary worker.

GS: But Kindred is giving jobs to people with gamer skills, too, right?

JL: Yes, on the tele-operation side. About 85 percent of the time, our algorithm can do everything on its own. But 15 percent of the time, we have a human in the loop who steps in and assists the robot for about a second and half, and then steps back out.

GS: When you’re recruiting for these people, are you recruiting in the typical places that tech companies look?

JL: These people have a wide variety of backgrounds and skill sets. They might be gamer types, but some of them have marketing degrees and some of them have engineering backgrounds. There’s also a pool of generalists, those jack-of-all-trades kind of people.

GS: But they need to have pretty good dexterity, right?

JL: I don’t think it’s highly required. A lot of it is just point and click.

GS: Well, on that non-techy note, Jim, thanks so much for your time.

JL: Thanks very much, Gregg.

This interview has been edited for content, length and clarity.