Internal politics had supposedly never played much of a role in the tangled web of companies that makes up the world’s largest furniture retailer. But when Inter Ikea, little-known owner of the brand and concept, acquired the product range, design and manufacturing businesses in 2016 from its more famous sister company, Ikea Group, Torbjorn Loof was struck by the infighting.

The chief executive of Inter Ikea says: “In the midst of everything, we also saw a bit of what we call political behaviour in the company. In the beginning that surprised me. When you work in Ikea you don’t know how to handle that because this was something new.”

The 53-year-old is running a franchise system that decides everything: from which products are on offer and what the stores look like, to the famous catalogues and flat-pack design. But rather than use his new-found power and influence, Mr Loof took a different approach.

“Of course, it’s easier for the party who in our case acquired resources, acquired influence . . . You need to understand and respect the partner that you are doing the deal with: to say what do you need and what’s your perspective on this? You have almost to put yourself mentally in their shoes,” he adds, in an interview in the store in Almhult, the southern Swedish town that was the birthplace of Ikea 76 years ago.

Mr Loof was raised in the nearby hamlet of Pjatteryd, and has worked at Ikea for 30 years in a variety of roles from purchaser and manager in Italy, to head of Ikea Sweden, the company at the heart of the empire that designs its products and was part of the 2016 deal.

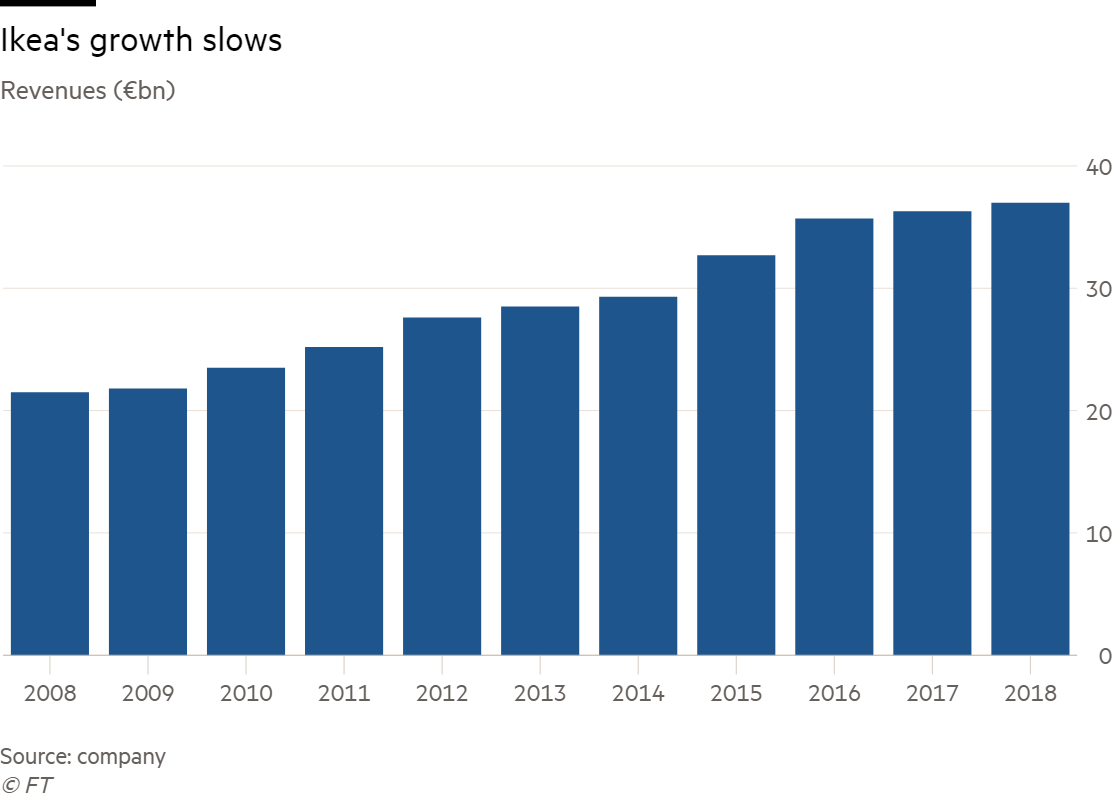

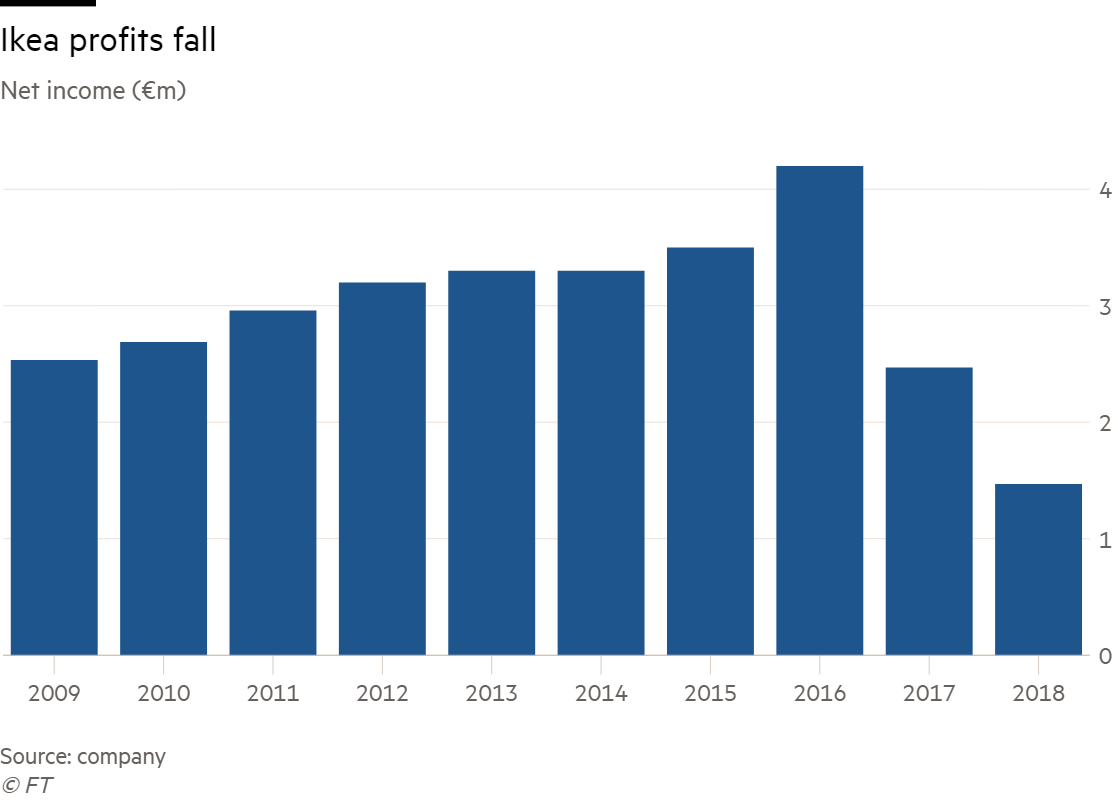

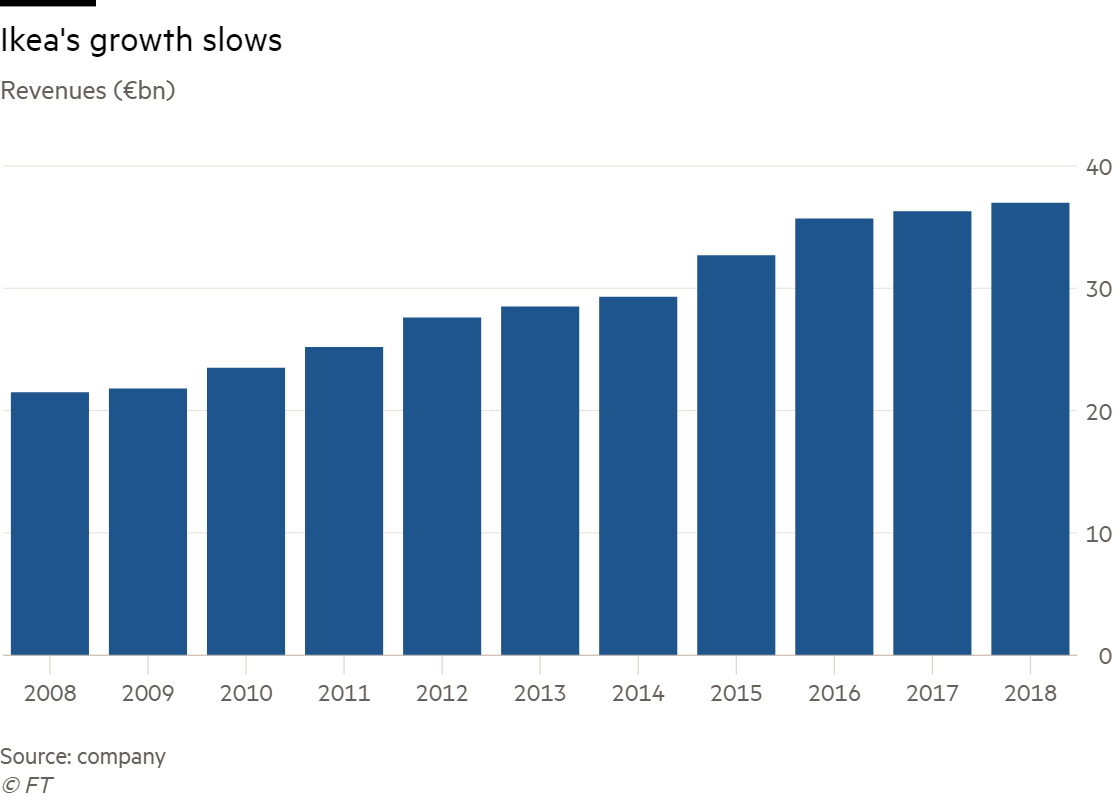

That acquisition — completed a year after he became chief executive of Inter Ikea — was in large part designed to help the company deal with the external forces buffeting the company in common with other retailers: online shopping, reduced footfall in stores, and increased urbanisation.

Mr Loof is now engineering the biggest transformation Ikea has undertaken by changing its famed business model that has brought it so much success. Having giant out-of-town warehouses, where shoppers pick their own furniture and then build it at home, underpinned Ikea’s solid profitability for seven decades.

But now it is looking increasingly at city-centre stores, online shopping, home delivery and assembly, and more radical ideas such as leasing furniture and selling on websites such as Alibaba. Mr Loof says that challenging such a successful status quo is tricky, especially as the company does not have all the answers on what the new retail landscape will look like.

“You need to get people on board in the ‘why’ part, why we are doing that, and also mobilise people to have energy in being part of this journey, not seeing it as ‘here we have an answer, OK, now I know what to do’- but actually you have to be part of this journey together with us.” He acknowledges that the company did not focus enough on the “why” at the beginning, preferring to get on with things before realising it needed to do more communication. “We made sure that the vision and the purpose were very, very clear. Not spending too much time on what sometimes is in the middle of things — all the strategies and plans, and all of that had to come later.”

Meetings of all the company’s leaders were called several times a year, and all were allowed input on how their part of the business would change, rather than having “a brilliant PowerPoint that says we [have] got the answers”. Mr Loof says it was important to put dates on when things would be decided, even if it was uncertain as to whether the solution was definitive. As a CEO used to delegating, he says it also became necessary for him to examine all proposals himself to stay on top of the details.

Recommended

Doing the merger, changing the business model, and dealing with the decline and then death of founder Ingvar Kamprad was what he calls “a perfect storm”. He says he misses Kamprad, who founded Ikea aged 17, and his advice. Mr Loof recalls one of the last times he saw him, together with some other Ikea managers. Kamprad said it was important to be long term and “think about where should we be in 200 years?” The managers smiled at his exaggeration and asked him if that wasn’t too much. “Yes, of course”, he said, “but then you make the short-term plan: that means the next 100 years”.

The Inter Ikea chief says that one of the toughest tasks is encouraging the entrepreneurship that characterised the company’s early days. He concedes that the decade-long period of growth in the early part of this century stifled Ikea’s creativity and recalls going to see Kamprad a few years ago when sales suddenly hit a bump.

“I was a little bit worried. I said to Ingvar: ‘sales are not growing’, and then he looked at me and just smiled and he said: ‘wonderful! Crisis!’ So, there is this kind of [attitude] to love the crisis because the opportunities in the crisis are that you get more creative,” he adds.

Since then, it has experimented more with what Mr Loof calls the “phygital” — the place where the physical and digital worlds of shopping collide. It has released an augmented reality app to allow you to visualise how Ikea furniture would look in your house as well as a virtual reality kitchen in some stores to let customers test set-ups instantly.

The transformation has not been without its mistakes. Mr Loof early on championed a new store format, pick-up and order points, designed for places such as the Canary Islands where Ikea would not build a full-store warehouse. Successful in remote areas, it soon brought them to bigger cities in countries such as the UK where they became unpopular with customers for the additional costs and not offering the full product range.

Out of that, Mr Loof says the company realised it needed different shop sizes — so it developed warehouses of 5,000 and 10,000 square metres (the Almhult store is 35,000 square metres) that contain most products but much less inventory than a traditional warehouse.

He says Ikea will do numerous trials in the next few years: “Even if we would be the best planners, we hire brilliant business analysts, the best strategists, I think we would not make it. So, we have to be the fastest learners . . . daring to test things and make mistakes, but also again correct them.”

Three questions for Torbjorn Loof

Who is your leadership hero?

I never thought of heroes in that way. But I have always been inspired by leaders that have big ambitions and a clear vision of what they want to accomplish. A leader that I had the privilege to work with was Ingvar Kamprad. His way to lead by being out in the business, talking to people and learning from reality was a big inspiration.

If you were not a CEO, what would you be?

I would either be a professional trumpet player or driving an excavator. Before I joined Ikea I played trumpet on a semi-professional basis. The career never took off but as they say, it’s never too late. The last couple of years I have been driving an excavator on my farm and realised that it’s a job I would love to do.

What was your first leadership lesson?

I was a newly appointed production leader in a factory at the age of 22. On my first day, my boss, a 64-year-old experienced production manager, came to me with a bucket of water. He put his hand in the water and said, do you know what this is? No, I said. That’s you when you are here and you will take some space, like my hand in the water. He then pulled out his hand and the water filled the space of his hand. He then said, when you leave this is how much we will miss you. My first lesson was to always be humble and realise that once you leave, life goes on.