By many metrics, 2018 was a rough year for brands. In a politically divided, financially tumultuous time, a victory with one audience might necessitate alienating another, while a business-savvy move could mean triggering customer outrage. Balancing the concerns of modern shoppers has never been trickier. Even some of this year’s “winners” felt the burn.

Companies saw store and brand closures, the loss of consumer trust and loyalty, and mounting concerns about privacy, politics, and sustainability. From J.Crew to Toys R Us, from Ivanka Trump’s eponymous brand to Burberry to Facebook, major brands felt the sting of 2018 in a variety of ways: pain apparent in their bottom lines and more philosophical wounds that could shape business for years to come.

But some companies did manage to come out ahead over the turbulent 12 months. Cultural wins for Dick’s Sporting Goods and Off-White were as valuable as the financial successes of Casper, WeWork, and Amazon. From marketing coups to the rise of new business models, from brands sticking to their political guns to shifting what we value in fashion, a handful of familiar names might be looking at a slightly brighter 2019.

Here are the brands whose highs and lows tell the story of a hard-fought year.

In February, after a gunman opened fire at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, killing 17 students and faculty and injuring more than a dozen others, the nation was in gridlock over gun control. The heated debate demonstrated how difficult it would be to alter America’s gun laws without Second Amendment purists crying foul, and most agreed little would be done.

Dick’s Sporting Goods, though, did do something. Two weeks after the shooting, the company announced that it would stop selling guns to customers younger than 21, and that it would end the sale of assault rifles and high-capacity magazines. In a statement, Dick’s chair and CEO Edward Stack said the decision was because of Parkland: “Our thoughts and prayers are with all of the victims and their loved ones,” he wrote, “but thoughts and prayers are not enough.”

But thoughts and prayers are not enough. We have to help solve the problem that’s in front of us. Gun violence is an epidemic that’s taking the lives of too many people, including the brightest hope for the future of America – our kids. https://t.co/J4OcB6XJnu pic.twitter.com/6VoKwJe8tH

— DICK’S Sporting Goods (@DICKS) February 28, 2018

Dick’s jumping into the gun control debate didn’t just stop at sales. The company also hired three lobbyists to push for gun control in Congress and destroyed all the weapons it stopped selling — a clear message about its attitude toward the inventory. In a year when many brands got more socially involved than ever, Dick’s big risks put it in the running for the most politically active brand of the year.

Although Stack stated he supports the Second Amendment and is a gun owner himself, Dick’s has since been painted as an enemy by the National Rifle Association; the National Shooting Sports Foundation even revoked the company’s membership. These moves have, of course, affected the company’s bottom line, and major gun companies now refuse to do business with Dick’s.

Its shareholders have also challenged Stack, likening his decision to “willfully giving up money.” Still, Dick’s continues to pledge corporate responsibility. Stack has said that despite gun shoppers feeling alienated, “we, as a company and a board, stand by our decision.”

In July, the first daughter announced that she was finally pulling the plug on her namesake fashion brand. Trump said the decision was because she needed to focus on her job in Washington. But the Ivanka Trump fashion label had been plagued with controversy since her father first took interest in public office.

Back in October 2016, women incensed by Trump’s Access Hollywood tape organized a boycott on Trump family businesses, dubbed #GrabYourWallet, which heavily targeted the Ivanka Trump label. The boycott hurt sales, which led to stores like Nordstrom, Belk, and Hudson Bay dropping the brand from their stores or websites.

The Ivanka Trump company claimed that sales were up, and even tried to cut wholesalers out. It opened a small store inside New York’s Trump Tower and started selling products directly from its website last year. Still, the brand could not escape controversy and was plagued with ethics questions regarding its relationship to the White House and labor violations among its numerous subcontractors.

The Ivanka Trump business continues to live on: Ivanka trademarks are still being granted in China, allowing Trump to make money in China off of Ivanka-branded wedding dresses, handbags, and jewelry. Those in the Trump resistance movement, though, see the shuttering of the brand as a victory.

Earlier in August, American mattress giant Mattress Firm filed for bankruptcy and announced it would have to close most of its 3,000 stores. The cause was clear: While Mattress Firm was struggling with customer disinterest and costly overhead, the mattress business had been successfully disrupted. There are quite a few entrants to the space, but direct-to-consumer sleep giant Casper has come out on top, boasting more than $600 million in revenue since its 2014 debut.

Casper has managed to make mattresses a sexy, branded purchase. This year, though, it expanded beyond mattresses and debuted more linens, pillows, and a new line of furniture as it looks to conquer the sleep economy. By branding sleep as a luxury and wellness commodity, Casper has proven that customers are willing to spend on sleep. It’s now leading this $30 billion cottage industry.

The mattress company’s rise illustrates the current staying power of digital direct-to-consumer brands, but this year Casper also tested the limits of retail by selling the unthinkable: sleep itself. Over the summer, it debuted its experiential retail concept, the Dreamery, where customers spend $25 to take a Casper-branded nap for 45 minutes.

While commodifying a basic human need seemed horrifying at first, the Dreamery is an experience that even one of the most skeptical of editors enjoyed.

Can a former-favorite clothing company successfully make a comeback after years of falling out of fashion? 2018 was a tough year for J.Crew, and it’s been hard to determine if the answer to this question is a yes or a no.

After years of plummeting sales, store closures, and flight of executives, J.Crew promised a fresh relaunch this fall. The classic American mall brand had also started to roll out initiatives from its newly appointed CEO, West Elm’s James Brett, who was working to get the brand on track. Part of Brett’s vision included lowering prices and making clothes with a casual-feminine touch, similar to J.Crew’s popular sister brand, Madewell, instead of leaning on J.Crew’s typically preppy roots. Brett also put the company’s lower-end label, Mercantile, on Amazon.

This brand revitalization came to a swift halt in November, though, after Brett parted ways with J.Crew, citing disagreements with the board. The Mercantile label has also been discontinued, and four board members are now splitting the position of CEO.

Many are doubtful J.Crew can survive yet another rebrand, and others compare J.Crew’s attempts to reinvigorate as “rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.” But in 2019, J.Crew has bigger problems than figuring out its brand voice: The company will need to reckon with nearly $2 billion worth of debt. If disagreements on the executive level and unimpressed customers won’t kill J.Crew, the money it owes very well could.

In 2018, the hottest brand in the fashion world was not a legacy fashion house. Instead, it was streetwear brand Off-White, the company of former Kanye West creative director and current Louis Vuitton menswear artistic director Virgil Abloh. It was founded in 2012 and is best known for its $1,000 sweatshirts.

This year, e-commerce platform Lyst named Off-White fashion’s hottest brand. Abloh’s recent appointment to Louis Vuitton certainly helped him gain mainstream name recognition, but Off-White clothes are immortalized by streetwear obsessives and Rihanna alike.

This year, Abloh’s popularity has exploded. The Nike x Off-White collab from this summer has been marked up about 450 percent on resale sites and everyone wants to work with him: He has collaborated with brands like Ikea, Rimowa, Timberland, Equinox, Kith, and Champion.

With all of Off-White’s visibility, some wonder if the collab king’s brand will become diluted and lose its value. The answer is probably not. Abloh is the first African-American artistic director at Louis Vuitton, bringing some much-needed diversity to an industry that hardly understands what that word means.

Plus, as high-end fashion brands look to younger audiences to reimagine what cool is, streetwear has become synonymous with luxury. The products that customers talk the most about are not handbags or dresses, but sneakers. Streetwear has been a boon to the luxury industry; demand for a name like Abloh likely won’t slow down any time soon.

Over the summer, Burberry proudly reported in its annual report that it had earned $3.6 billion in revenue last year. Along with this number, the British fashion house also revealed that it had destroyed $36.8 million worth of its own merchandise — a common practice in retail that supposedly helps preserve a reputation of exclusivity.

This news about Burberry destroying perfectly usable merchandise, including $13 million worth of makeup, was met with consumer outrage. Shoppers vowed to boycott Burberry over its wastefulness, while members of Parliament demanded the British government crack down on such practices.

The uproar was effective, and two months later Burberry said it would no longer destroy its products. While it pledged a commitment to sustainability and jumped on the train of fashion brands swearing off fur, Burberry spurred countless reports to expose the frequency at which unsold merchandise is destroyed. The practice was unfamiliar to consumers, but now it will likely be associated with Burberry for a while. That type of bad press is sure to leave a mark.

The closure of Toys R Us had people marching in the streets after it was revealed that more than 30,000 store employees would be losing jobs without severance, while those on top reaped millions.

The troubled toy company filed for bankruptcy in September 2017, and after difficulties finding a buyer or lender for a debt restructuring deal, it liquidated the business completely. Store associates were told that because of Toys R Us’s financial troubles and debt, employees would not receive severance, but Toys R Us executives walked away with millions of dollars in bonuses.

Having tens of thousands of workers unemployed was indicative of the struggling retail sector, but Toys R Us employees were particularly incensed because the venture capital firms that bought the company in 2005 reportedly also made an enormous profit by purposely mismanaging the company.

The fight of Toys R Us retail workers became a national story about the working class battling against Wall Street greed. After months of protests and pressure from politicians like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, two of Toys R Us’s private equity firms finally agreed to allocate $20 million in a severance fund for store employees. While it’s a step in the right direction, retail advocacy groups note it’s not even close to the amount of money workers are owed.

In 2018, coworking space giant WeWork doubled its size, expanding from 200 locations to 400. WeWork is now the largest office space tenant in Manhattan, London, and Washington, DC, and it boasts a network of 400,000 members in 26 countries.

WeWork modernized the coworking space, and the sector now includes countless copycats. With its $45 billion valuation, it has huge ambitions in the real estate space. This year, though, WeWork also demonstrated that it wants to expand the entire sharing economy to its advantage. Co-founder Adam Neumann said he intends to apply the WeWork concept to whole communities around the globe, with WeWork schools and WeWork apartments. It won’t be long before WeWork has a hand in all aspects of how its members live.

Such ambitions come with growing pains: The company killed its unlimited beer and alcohol policy this year, following a suit that alleged that the company’s “frat-boy culture” led to a problem with sexual harassment. But WeWork’s attempts to change its culture signal that it’s approaching expansion seriously.

It’s no surprise that Amazon has become the kingpin of retail; it’s where nearly half of all online shopping in 2018 happened and it continues to stake its claim in American retail with new stores. With its expansion of Amazon Web Services and Alexa-powered devices, Amazon is unstoppable.

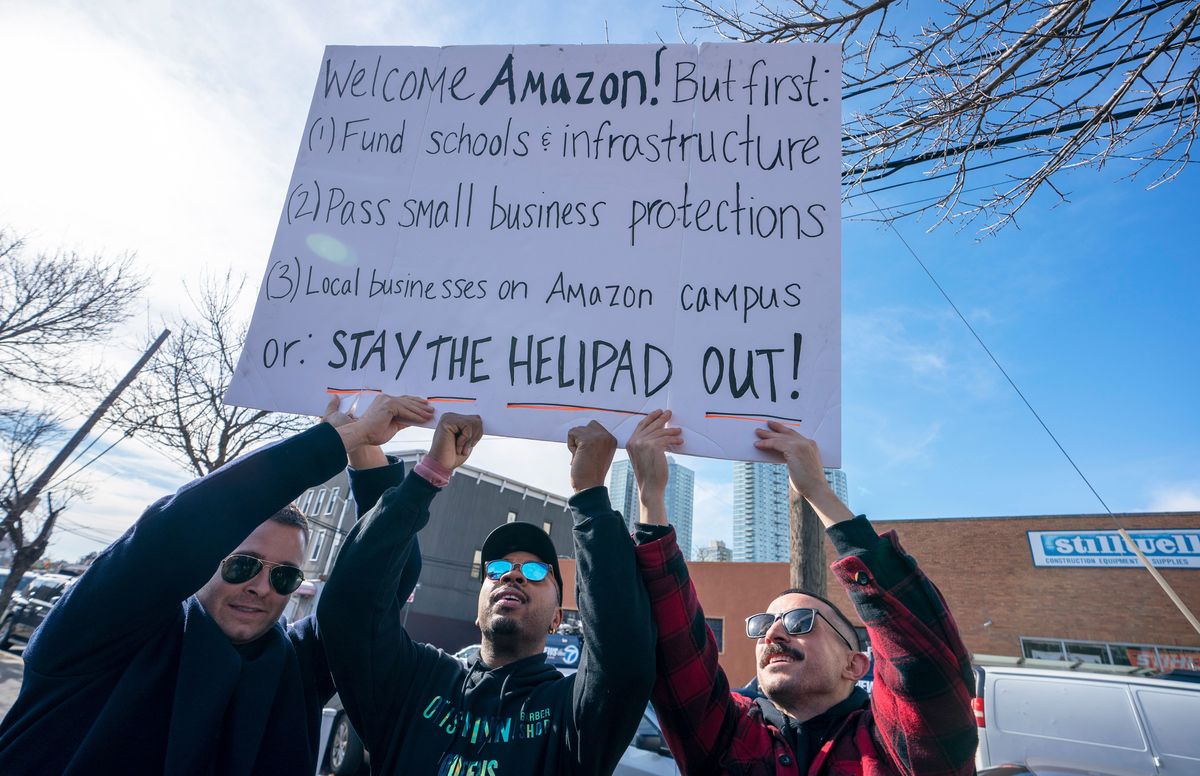

But Amazon dominated more than tech and retail in 2018. After announcing it would expand from its Seattle headquarters and find a new home for its “HQ2,” a second large office location, Amazon successfully ran one of the biggest marketing campaigns of the year.

Two-hundred-thirty-eight different cities across the country, trying to win Amazon’s beauty pageant, pledged everything from tax benefits to free parking to exclusive zoo memberships to creating a new town in which Jeff Bezos could be mayor for life.

In the end, it decided to split its HQ2 between New York City and the DC suburb of Arlington, Virginia — a move it may have landed on months before cities began courting the company, and may have pitted them against each other to get New York and Virginia to up their antes.

Even though the company treads in problematic territory, like reportedly mistreating employees, and has faced pushback from (former) Prime subscribers, the HQ2 spectacle proved that Amazon has enough power to make entire cities bow before it — and that powerful people are okay with overlooking Amazon’s controversies.

What with the Cambridge Analytica scandal, data breaches, the founders of Instagram and WhatsApp fleeing, and violence as a result of misinformation spread on its platform, Facebook has had a devastating 2018. It’s not surprising that Americans trust Facebook less than any other tech company. And yet, despite its poor track record, the social media debuted its first gadget, the Portal smart speaker, in October.

Facebook’s leap into the smart speaker category was clearly an attempt to compete with Google and Amazon. According to eMarketer, more than 61 million Americans used smart speakers this year, and Marketwatch believes the industry will earn $30 billion by 2024.

Facebook’s smart speaker debut also sent a message: It wants to bolster friendly communication. The Portal can video chat, unlike Amazon’s Alexa devices, and its high-def “Smart Camera” enhances the experience by following a user around the room instead of making them sit in front of a laptop or phone.

But the timing of the gadget’s rollout was tone-deaf. Facebook promised users the Portal is “private by design,” says its gadget does not use facial recognition technology, and that the company “doesn’t listen to, view or keep the contents of your Portal video calls.”

Still, all of these prompts are made with the assumption that shoppers would trust a company like Facebook to sell them such a gadget to begin with — that they would allow and even want a Facebook-made device designed to constantly listen to them and track their movements.

As one commenter noted on Facebook’s announcement, “Oh hell no. Mark, when you can secure FB, Messenger and your other social media for your customers and users then I still would not put this device in my home.”