We’ve heard it all before—some new, groundbreaking technology is going to change the way we live and work. In fact, we’ve heard these claims so many times that it’s only natural to feel skeptical of them. While we may still be waiting for self-driving cars to make our gas guzzlers obsolete, amazing technologies are already here to change the way we experience a place.

This technology has been used in test cases in journalism, but never has AR been the backbone of a series of stories and so deeply integrated into the editorial process.

To see the evolution of how we can use 3D imagery and aspects of virtual reality in city planning, retail, education, and journalism, look no further than augmented reality (AR). This technology has been used in test cases in journalism, but never has AR been the backbone of a series of stories and so deeply integrated into the editorial process.

This is why I jumped when Quartz approached me to use new technologies to build experiences in journalism. Our goal was simple: use AR to better understand what cities will look like in 2050.

Melissa Lyttle

Steve Johnson at Cedar House in Yoshino, Japan

What we did

We chose AR because, compared to other types of immersive technologies like virtual reality or video, AR is better at showing context—the relationship of our stories published right in your living room to scale. This is a big deal. Context is how we learn. It is how we put our views into perspective and build healthy discussions on complex issues. And that’s why we chose to use it for the 2050 Project.

These models you see on your phone aren’t just architectural renderings—they are photorealistic models. They show how a building fits in living with the environment around it, how people are using it. They offer a snapshot in time that reflects the role of a particular place in its community, and how that place evolves.

Bringing this technology to a newsroom is exactly why I started SeeBoundless. It’s why I spent many late nights experimenting with how we take a technology that not normally used for journalism and build a process to do so. We can now see how a place evolves with context and perspective. You can picture what Copenhill will look like in 10 or 15 years, or what downtown LA looked like before Disney Hall was built.

The models inform the future, too—you can begin to build your own understanding of why community-driven solutions help lift cities into becoming healthier and more prosperous for the people who live there.

How we did it

We created the AR models using a process called photogrammetry. First, we captured hundred of images of the building, shot from the ground and by drones. Then, AutoDesk Recap Photo, (the photogrammetry software we used), looked at every pixel in each photo and compared them across all of the photographs to measure distance. It then built hundreds of thousands of triangles that are made up of these measurements and built a 3D model. It then took the pictures to overlay a skin or texture onto the 3D model, which gives you the final product that you see on the Quartz site or app. We took all of this data and polished it in 3D modeling software to add a base to set the object on, annotate any interesting features and make sure all of the photos aligned correctly. The final result: a scaled model that you can place in your living room to see just how these structures interact with their surroundings and yours.

Melissa Lyttle

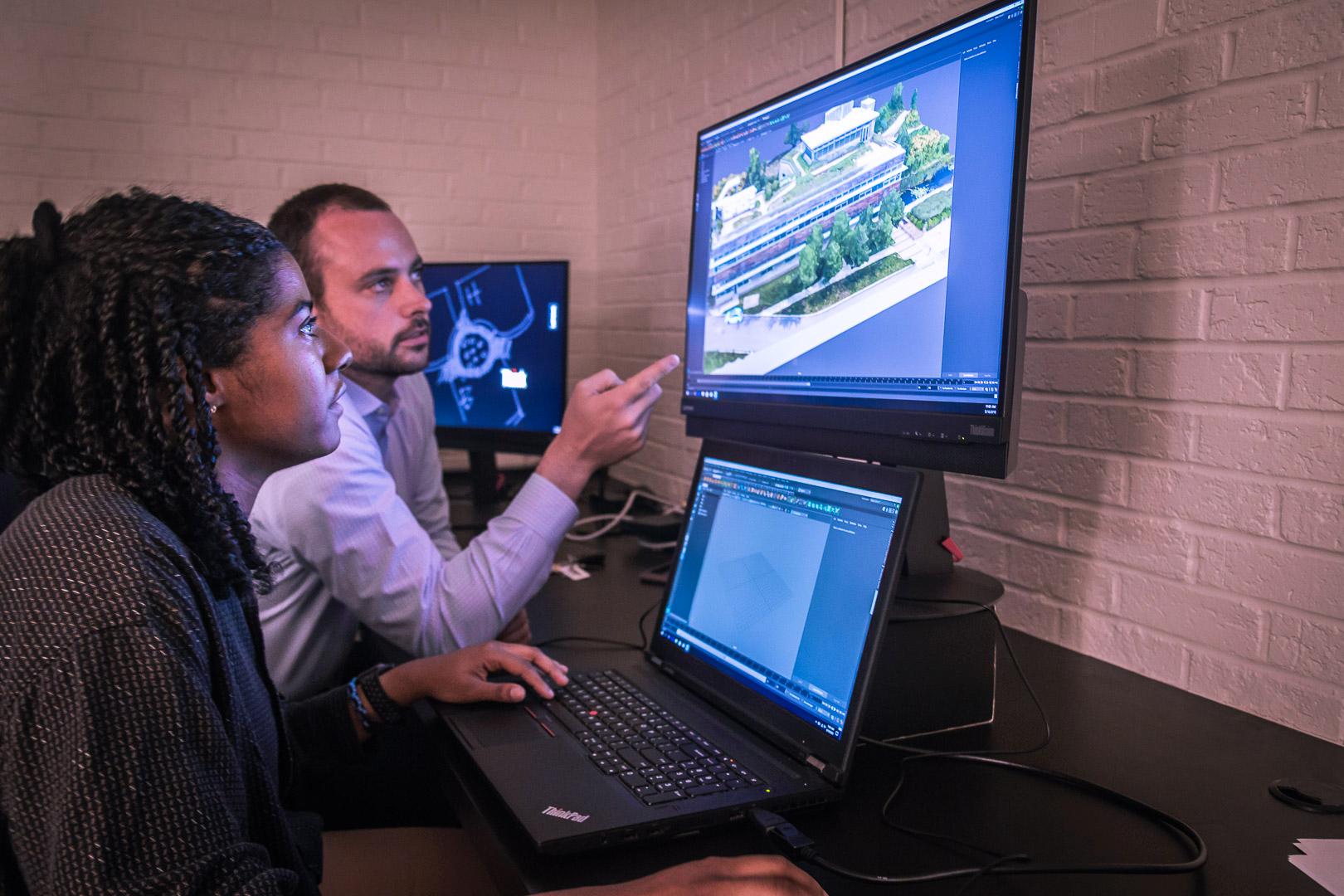

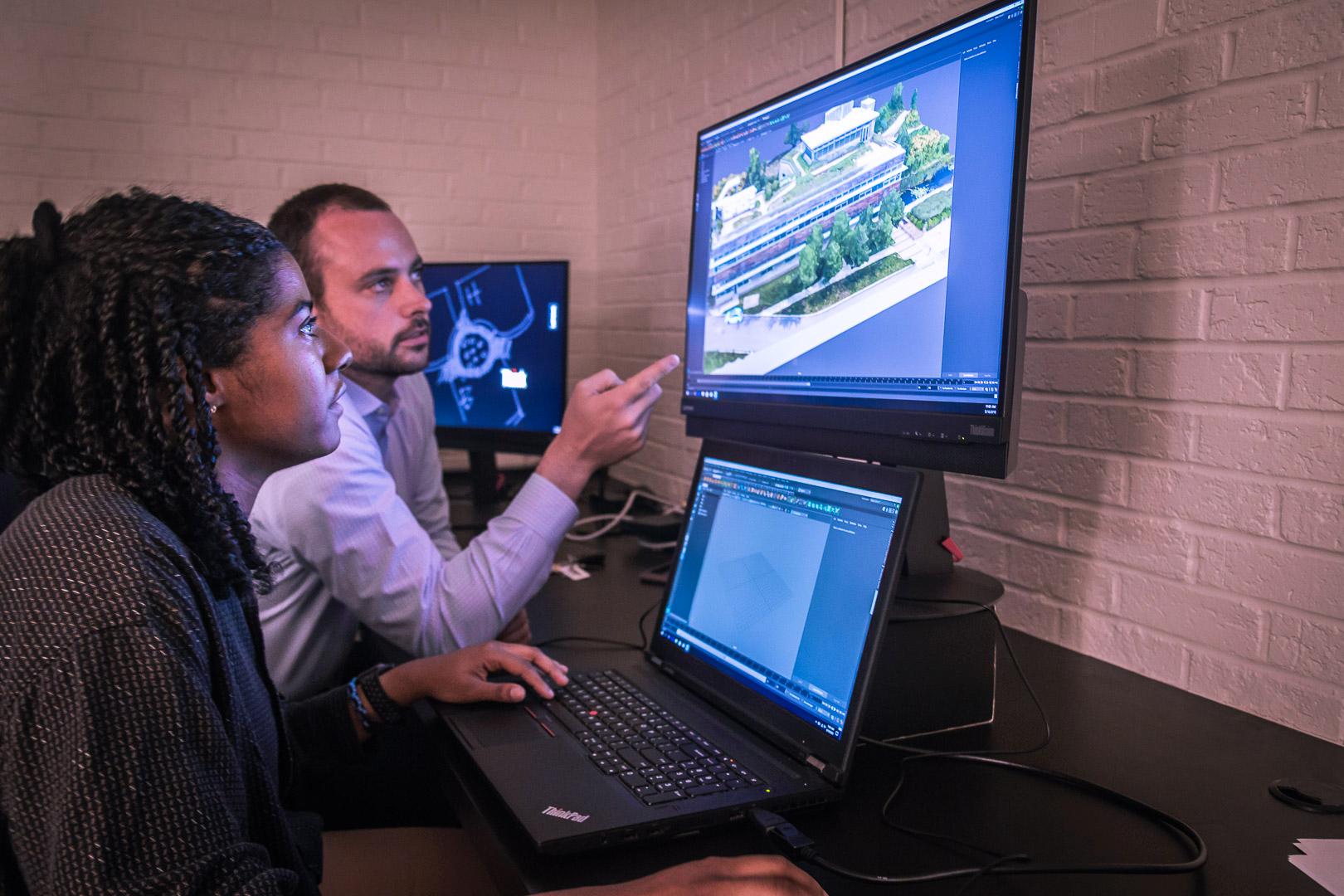

Alexis Barnes and Steven King

It took months of trial and error to figure just how many photographs we needed and from what angles and altitudes.

To accomplish this, we partnered with two amazing journalists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Steven King and Alexis Barnes who run the Emerging Technologies Lab. Together, we built the production guidelines to figure out how many photos we needed to work with our software, and from what angles to take them.

Then it was time to capture the images. Melissa Lyttle, our drone pilot, and I traveled to all of the buildings featured in the 2050 Project. In total, we logged more than 40,000 miles of travel across four continents.

Melissa is an expert photojournalist who worked with me to determine how we could safely fly exact patterns (following FAA guidelines in the US and working with international airspace regulations and permits) around all eight of the buildings to capture the necessary angles for our software to build the 3D models.

Steve Johnson, SeeBoundless

Melissa Lyttle

To capture images of the Freddy Mamani buildings in El Alto, Bolivia, we not only had to work at an altitude of 14,000 feet (which left us feeling as breathless as if we were running a marathon in New York City) but also collaborated with our fixers and the community to ensure we were not disturbing residents, business owners, and locals.

Looking ahead, we can see many more uses for photogrammetry and 3D models. They could help teachers bring new worlds, historic artifacts, fictional characters into classrooms. They could help researchers measure 3D spaces like forests to estimate their biodiversity or cities to measure how pollution spreads. Coders can use these models to create better simulations for first responders to plan and model how they would respond to a disaster using actual buildings in actual cities that they are protecting.

The 2050 Project is not just about how cities will build solutions, but also how we will use the best tools available to explain and understand what problems lay ahead.