|

| (Image source: Lenovo) |

How did Lenovo become one of the first companies to market with a standalone mobile VR headset?

Whether the industry realized it or not, virtual reality was in a transitional phase in 2018. After a boom in interest the ’90s failed to materialize into widespread adoption, VR exploded into the public consciousness again circa 2012 thanks to the Oculus Rift VR headset- a Kickstarter project that later boomed into a billion-dollar acquisition by Facebook.

The success of the Rift and other tethered headsets such as the HTC Vive and the Sony Playstation VR showed there was definite interest, particularly among video game enthusiasts, in VR. But the VR industry wanted more. Seeking to find a home for VR in enterprise spaces beyond gaming, such as in design engineering, product design, healthcare, retail, and even social media – the industry was faced with a choice: Either let VR remain a tethered experience, dependent on high-end desktop computers or gaming consoles to operate, or turn VR into a mobile experience – essentially making the headsets themselves into self-contained systems.

The industry chose to go mobile. While cheaper VR options such as the Samsung Gear VR had already taken the mobile approach, essentially placing smartphones inside of a pair of binocular lenses, consumers were waiting to see what standalone headsets would do.

While many anticipated the successor to the Oculus Rift to be a more powerful, PC-based headset, the now Facebook-owned Oculus surprised many in Fall 2018 when it announced that the Oculus Quest, its next-generation headset, would be a mobile standalone headset.

With HTC and most VR headset makers following suit the future of VR is a bit clearer.

But it was actually Lenovo, a company that hadn’t previously released a high-end VR headset, that came to market first with a standalone VR headset. Priced at $400, the Lenovo Mirage Solo was marketed as the first standalone VR headset to feature Google Daydream – an Android-based VR operating system, as well as Google’s WorldSense technology for providing six-degrees of freedom (6DoF) tracking.

The headset was released to favorable reviews. And while the Mirage Solo hasn’t become the go-to hardware for mobile VR, the headset itself and the story of its development represent a pivotal point in VR’s reemergence as a viable enterprise and consumer technology.

Project Tango

“[Lenovo has] a long-term view that AR [augmented reality] and VR are a critical space and that VR is a natural evolution of computing,” Jeffrey Witt, a Manager at Lenovo, said. “AR and VR are just new ways to do what you love as a consumer – interacting with content and creating content.”

While Lenovo had demonstrated some seriousness around VR with the release of its Explorer mixed-reality headset for Windows PCs as well as Jedi Challenges – a Star Wars augmented reality game and accompanying hardware – there hadn’t been anything to suggest it was interested in creating its own VR platform until the announcement of the Mirage Solo.

Witt said the inspiration for the standalone headset came from Google’s now-defunct Project Tango. Tango was an AR platform that used computer vision algorithms, combined with a smartphone or mobile device’s camera, to allow the device to detect its position relative to the world around it – sort of a self-contained GPS. If successfully implemented, Tango could allow smart devices to facilitate AR applications as well as perform navigation, mapping, and environmental recognition tasks.

In 2016, as part of a partnership with Google, Lenovo actually released a smartphone, the Phab 2 Pro, that employed Google Tango technology. But in 2017 Google ended its support of Tango and phased it out in favor of its own ARCore development kit for creating AR applications.

But even without Tango, Witt said that Lenovo had laid the foundation of what it wanted to do next. “The spatial sensing technology used in Tango is what inspired the tracking and motion sensing in the Mirage. It’s very similar technology,” he said.

Smartphone Inspiration

The question for Lenovo was how could it take a different approach to mobile VR, one that wasn’t being taken by the likes of Oculus, HTC, or Sony. “They all focused on gaming,” Witt said. “We looked at what we know in categories like tablets and phones to understand what consumers gravitate toward in terms of stickiness and repetitive use cases. [Phones and tablets] are things that don’t need immersion but are used over and over and over again.”

|

| The technology behind Lenovo’s Phab 2 Pro phone laid the foundation for the Mirage Solo. (Image source: Lenovo) |

That meant taking a look at the features people used the most on their phones and tablets – things like sharing photos and videos, web browsing, and even playing games. But could a VR headset become the same sort of one-stop shop that a smartphone can be?

“At the very beginning there were already smartphone-based experiences that our team had tried and the conclusion was that it is very good for getting people on board, but not good at all for getting people to return and understand VR and its true potential,” Witt said. “The Oculus Rift is not scalable; you can’t take it to a friend’s house. What motivated us was that we could create a complete solution for getting into VR.”

Comfort is a Must

The first step to doing that is creating something comfortable. No one bemoans the heft of the 140-gram smartphone in their pocket, but wearing a 1- or 2-pound headset for any extended period of time is sure to draw a fair number of complaints.

“We focused on a few key areas that all fall under comfort: Easy setup, plug and play, standalone, no PC, and no cable,” Wahid Razali Consumer Product Marketing Lead at Lenovo, said. “Comfort in fitting is everything. It’s what’s helping you get immersion and a better sense of presence.”

Razali said creating comfort in a VR headset is a careful act of engineering that involves juggling several aspects. “Weight balance is a very big challenge because you have to balance absolute weight, which is a function of components and materials, and also industrial design,” he said. “For example, should we have a ring or a strap to hold the headset in place? The downside of the strap is the longer you wear it the more you feel weight on the front.”

Eventually the team settled on the Mirage Solo’s current design – a head strap with a built-in knob for adjusting the tightness and fit. “We tried to build a weight balance that would make the headset feel lighter than it is,” Razali said. Doing this involved extensive user testing – taking feedback from subjects from different regions of the world to sample of a variety of head shapes for calculating things such as the optimum padding density for the headset, for example.

“We paid attention to male and female hair because we wanted to make sure our dial adjustment knob mechanism would not entangle with hair,” Razali explained. “Making sure no hair could get stuck in there meant we had to be precise in modeling and engineering and had to select material with less friction.

“We overweighted the knob so it lifts the from the headset. The way we designed the attachment mechanism between the headband and the processing unit itself, we made it purposely able to wobble so that it can adjust the eye-to-lens distance so you can be in focus no matter your interpupillary distance or if you were wearing glasses…You can’t have miscalculation of the lenses. The assembly process for a VR headset is many times more demanding than, say, a simple camera on the phone. In this instance you are in the picture so if it’s offset and the tracking is not good you will feel it…planning for glasses turned out to be an advantage because we ended up with a bigger eyebox, which gave us more space for air dissipation and avoided having to use more foam.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

Heavy…but Wearable

A typical Lenovo product goes from three to four revisions from proof-of-concept to an actual tooled version. The Mirage Solo by contrast, went through 14 revisions, “which is very unusual for us,” Witt said.

The final Mirage Solo weighs in at 645 grams, which Lenovo acknowledges places it on the heavier end of the VR headset spectrum (the Oculus Go weighs about 467 grams by comparison), but it also offers a leg up on some of the same headsets released at the time, most notably inside-out tracking (meaning the headset can track head movement without external sensors).

In hands-on tests done by Design News, the weight is tolerable, though perhaps not over the very long periods. But Lenovo’s hope is that users will embrace the headset for its overall comfort and aesthetic. Rather than the sleek black look adopted by the more hardcore headsets or the casual fabric look of the Google Daydream View, the Mirage Solo sits somewhere in between with a white and grey plastic finish more akin, again, to a smartphone or tablet.

We used a foam and polyurethane material for the casing,” Razali said. “You need to balance a few parameters that don’t necessarily come as a magic formula. The challenge was [the Mirage] needed a lot of prototyping testing because it’s a balance of materials, assembly solutions, rigidity, and color.”

Part of that was paying attention to early consumer insights. “For this headset to ever get mass adoption we needed to move way from the perception that it’s a nerd or geek’s product,” Witt said. “The white color makes it feel more like a wearable, something you can be seen in without feeling odd. It also helped overcome the aspect of it being such a big headset for consumers.”

Performance, for a Price

Lenovo decided early on that its partner, Google, would handle the software end so that Lenovo could focus on its core competency – designing the hardware.

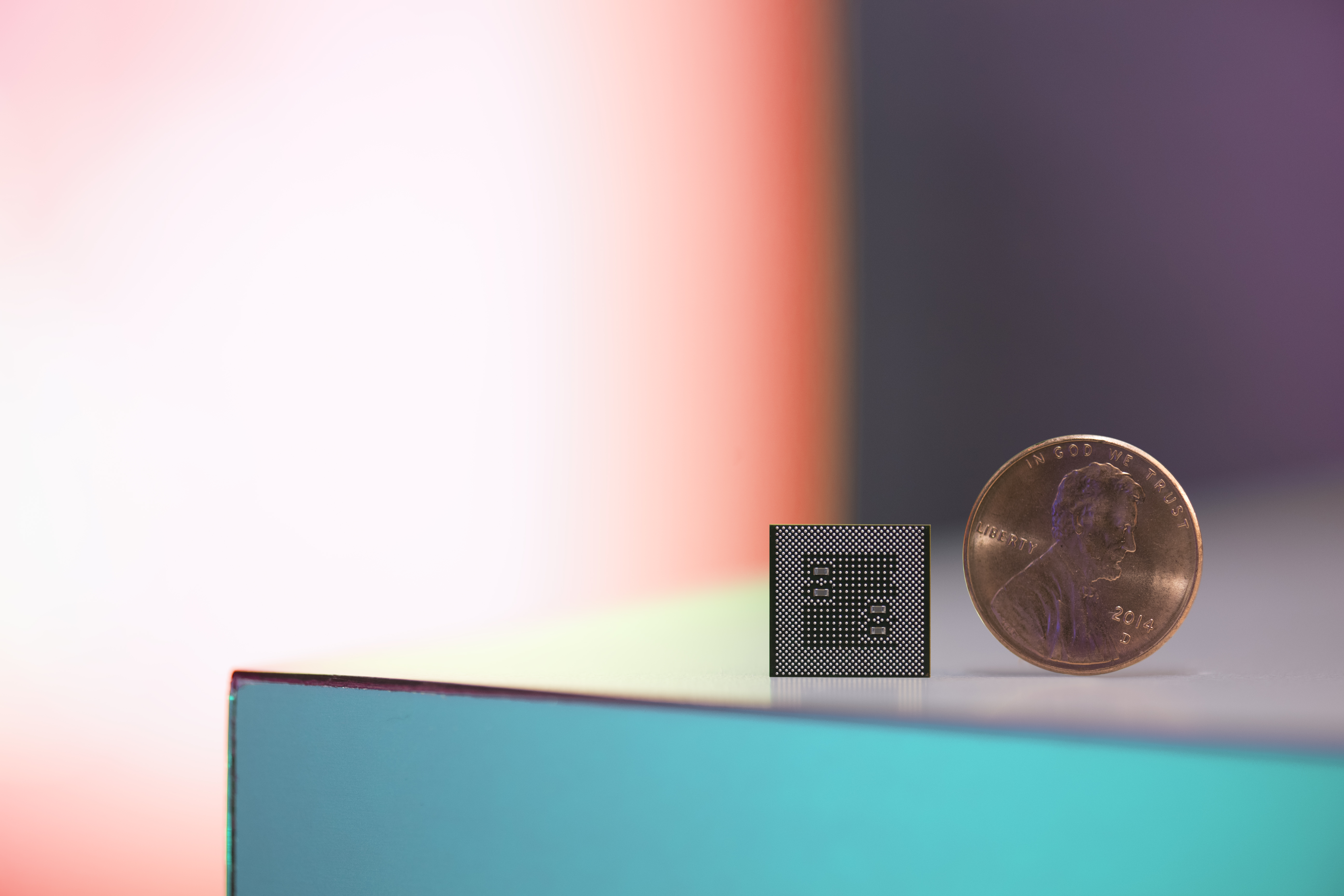

|

| The Snapdragon 835, touted for its ability to handle AR/VR applications, is the Mirage Solo’s core processor. (Image source: Qualcomm) |

“We focused on three areas of performance: processing power; display quality; and tracking quality,” Razali said.

The Mirage Solo’s processor is a Qualcomm Snapdragon 835, the same chip the drives the upcoming Oculus Quest as well as the HTC Vive Focus standalone headset. When it was initially released in 2017, the 835 was first touted by Qualcomm for being optimized for delivering mobile VR and AR experiences to smartphones and other devices. “We actually had Qualcomm participate in tuning and development of a specific heat dissipation design in the headset, so the chip is overclocked compared to how it is in a smartphone,” Razali said.

Other components, such as the display, needed to be created from the ground up. “One of the biggest challenges was getting the headset to an acceptable price point,” Razali said. “What drives cost up is lenses, camera, the processor, and display. We realized quickly that going with an OLED display would present a problem as far as hitting an acceptable price point. We went to LCD providers and created a custom display alongside engineers from Google.” The result was a patented display technology that Razali said outperforms OLED displays while still delivering a competitive 110-degree field of view, 16:9 aspect ratio, and 1280×1440-pixel resolution.

The cameras that provide the Mirage’s inside-out tracking capability whee another issue. “We’re not camera experts,” Razali said. So for this the company leaned on Google.

“The core design principle of the tracking has been done by Google. WorldSense builds on core principles of Tango and ARCore. The headset’s cameras sense the physical world and at all times know where features and points of interest are. There’s no AI that recognizes walls, floors, tables, ect. So what we were looking for was to make sure we start from a reference point and that any movement taken by the headset is very accurately tracked at all times. That’s probably the biggest immersion factor.”

The engineering team did have to make one compromise when it came to the Mirage Solo’s control. Rather than full 6DoF controllers that would be able to fully track the user’s hand movements in space, the company had to opt for three degrees-of-freedom (3DoF), meaning the controller can track position in space, but not motion.

“We actually wanted true 6DOF in the controllers, but then it was coming down us having a gut check,” Witt said. “Can we do headset that will cost $1000 or maybe more that will tick all these boxes? Probably. Would anyone buy it? Probably not.”

No Boundaries

Right now Witt said Lenovo’s research shows gaming as only the fourth most popular consumer application for the Mirage Solo – behind exploring and discovering, live events, and movies/video/TV at number one.

Witt said the most demanding vertical for the headset is in education. To support that, the company rolled out Lenovo Virtual Reality Classroom, a hardware and software suite built around the Mirage Solo that is aimed at allowed students to take virtual field trips or attend remote lectures and study via VR classrooms.

Lenovo also has pilot runs going on now around implementing the Mirage Solo in training, manufacturing, and simulation applications in the enterprise and commercial space. These sorts of applications could take advantage of a hidden feature buried in the Mirage’s Developer Mode settings – the ability to turn off the safety boundary that will only let a wearer move so far in any one direction. With this feature disabled a user could move freely around any size space and have the headset track their movement.

| Users have experimented with full room-scale tracking by disabling the Mirage Solo’s safety boundary controls. (Image source: Reddit / Hatrabbit Entertainment) |

“It’s possible today that a commercial developer could decide to build something for no boundaries. Users in warehouses, for example, could enjoy a same-scale space in VR,” Witt said. “The limit on commercial though is you need to build the software from the ground up.”

Witt and Razali declined to discuss plans of future iterations of the product, but Lenovo is regularly rolling out software updates. The Chrome web browser, not available at the headsets release, was later rolled out to allow wears to surf the web in VR for example.

“We built the Mirage Solo to be future proof. We have software driven by Daydream and hardware that will allow us to make the product compelling for more use cases in the future,” Witt said. “Anything that you can do in Android you’ll be able to do in VR one day.”

This future proofing, Witt said, will also help point Lenovo to the next stage: products that implement both VR and AR. “Everyone agrees AR/VR will eventually be one. But if we are strong in one we can be strong in the other,” Witt said. “ It’s critical to be moving toward that space in AR/VR-capable devices. The trick is finding the right proposition for consumers and the right price balance.”

Chris Wiltz is a Senior Editor at Design News covering emerging technologies including AI, VR/AR, blockchain, and robotics.

ESC BOSTON IS BACK! The nation’s largest embedded systems conference is back with a new education program tailored to the needs of today’s embedded systems professionals, connecting you to hundreds of software developers, hardware engineers, start-up visionaries, and industry pros across the space. Be inspired through hands-on training and education across five conference tracks. Plus, take part in technical tutorials delivered by top embedded systems professionals. Click here to register today! |