As most retailers know, revenue isn’t simply based on how many items you’ve sold. It’s a more involved calculation of how much each item costs you, the retailer, versus how much the item is sold for.

As most retailers know, revenue isn’t simply based on how many items you’ve sold. It’s a more involved calculation of how much each item costs you, the retailer, versus how much the item is sold for.

But the cost of each one of your products is an amalgam of the parts, as well as your overhead and everything in between.

Understanding the cost of goods sold (COGS) not only helps retailers see a full picture of their revenue, but it also brings about some benefits to the business—but more on that later.

Today, let’s focus on the four basic elements of COGS:

- What is Cost of Goods Sold?

- Why You Need Keep Track of Costs of Goods Sold

- What’s Included in Cost of Goods Sold?

- What You Need to Calculate Cost of Goods Sold

- How to Calculate Cost of Goods Sold

1. What is cost of goods sold?

Simply put, COGS is what it the cost of doing business—essentially, the costs to sell each product in your store.

The cost of a product is so much more than just the literal sum of its parts.

Yes, a product requires materials and parts, but it also requires labor. It also requires manufacturing the parts or buying them from third parties. It requires the cost of shipping said parts to your warehouse and assembling these parts. Not to mention the overhead: the human resources from labor, to rent, to equipment, electricity to run the operations, employees to sell said products in your store, as well as sales and marketing and finance and all the other departments.

That’s a lot. And that’s what it costs to sell things.

For example, if you sell a T-shirt, think about the journey that product takes before it even becomes a T-shirt all the way until it gets in the hands of your customer.

Before the T-shirt is even a T-shirt, it is thread. The thread gets turned into fabric and then gets dyed. And manufactured… and the T-shirt is packed nicely for the customer, then shipped. But wait—don’t forget the designers who created the look of the T-shirt. And the people who reviewed and approved it. And the models who tried it on. And the marketers who created the website, and the IT department provided a network for everyone to communicate. And so on.

Before the T-shirt is even a T-shirt, it is thread. The thread gets turned into fabric and then gets dyed. And manufactured… and the T-shirt is packed nicely for the customer, then shipped. But wait—don’t forget the designers who created the look of the T-shirt. And the people who reviewed and approved it. And the models who tried it on. And the marketers who created the website, and the IT department provided a network for everyone to communicate. And so on.

All for one T-shirt. All of these items cost money to create the T-shirt. So, your T-shirt isn’t simply a T-shirt—it’s the sum of all of these moving parts. As a result, these are all expenses that contribute to the end cost of the product.

Expenses you need to keep track of to ensure not only are you making a profit, but that net versus gross revenue is accurately measured.

Cost to make each T-shirt: $20

Retail price of each T-shirt: $30

———————————————————————–

Net profit of each T-shirt sale: $10

2. Why you need to keep track of cost of goods sold

It’s important to keep track of all expenses so you know the company’s gross versus net revenue. But there are many other factors to keep track of COGS as well as other line items.

The biggest of which is the government.

Tis impossible to be sure of anything but Death and Taxes,” from Christopher Bullock, The Cobbler of Preston (1716)

Sure enough, when reporting taxes, Uncle Sam (or your localized government equivalent) wants to know how much a business made so they can tax said business accordingly.

The good news is that COGS are business expenses—which means they don’t count toward your gross revenue. And COGS are an expense line item in your company’s income statement, otherwise known as a profit and loss statement (or P&L). By calculating all business expenses, including COGS, this ensures the company is offsetting them against total revenue come tax season. This means the company will only pay taxes on the net income, thereby decreasing the total amount of taxes owed.

A note on COGS and taxes: while high COGS means lower taxes, that is not the ideal scenario because it ultimately also means lower revenue for the company. It’s important to manage COGS efficiently in order to increase profits.

3. What is included in cost of goods sold

The cost of goods sold is essentially the wholesale price of each item, which includes the direct labor costs required to produce each product.

Materials:

- The individual costs of all parts used to build or assemble the products

- The cost of all the raw materials needed for the products

- The cost of any and all items purchased for resale and/or to create the product

Labor:

- The parts or machines required to create the product

- All supplies required in the production of the product

- Shipping parts and equipment to the warehouse to create the product, including containers, freight, fuel surcharges, etc.

- The workforce (people) who put the products together, ship the parts, etc.

- Warehousing costs, including rent, utilities, etc.

Operations:

- Office staff: everyone directly involved in the product

- Software, hardware, office rent, utilities, etc.

4. What you need to calculate cost of goods sold

Typically, the CFO or other certified accounting professional would handle these calculations because it’s not as simple as we’ve laid out in the example above. However, for the DIY CEO, calculating COGS requires a bit of information prep beforehand in order to report accurately.

Here’s what you need to calculate COGS.

- Valuation method. Whoever prepares your taxes should advise you on what valuation method you should use for your business: at cost, lower of cost or market, or other.

- Beginning inventory. What is the total cost of all your inventory of products at the start of your fiscal year? This should match the ending inventory for the previous fiscal year.

- Cost of purchases. [Total of all the products purchased during the fiscal year that is available to sell, including raw materials] LESS [anything taken for personal use]

- Cost of labor. The cost of employees directly associated with assembling the product. (Not back-office staff.)

- Cost of materials and supplies. Whatever costs are associated with making the products you’re selling.

- Other costs. All other costs no previously accounted for: shipping containers, freight for materials and supplies, overhead expenses (rent, utilities, hardware, software, etc.).

- Ending inventory. The total value of all remaining items still in inventory at the end of the fiscal year.

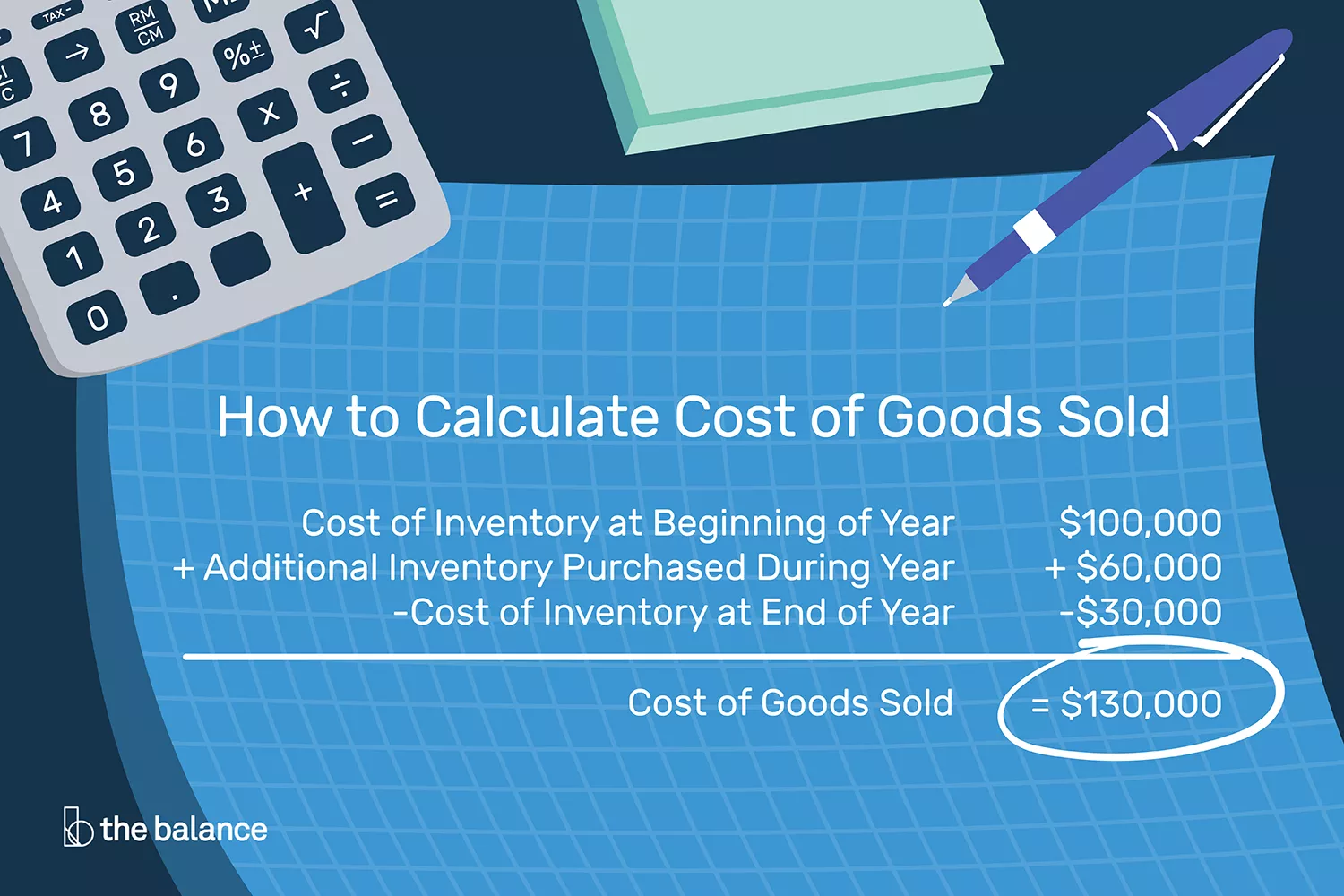

The basic formula: [ B + C + D + E + F ] – [ G ] = COGS

5. How to calculate cost of goods sold

Direct vs. indirect costs

When working with the numbers, it’s important to remember there are two types of costs associated with each product: direct and indirect costs.

As the names imply, direct costs mean all costs that are directly associated with the product itself. This includes the cost of raw materials or items for resale, cost of inventory of the finished products, the supplies for the production of the products, packaging costs and work in process, the supplies for production, and overhead costs, including utilities and rent.

Whereas indirect costs include labor (the people who put the product together), the equipment used to manufacture the product as well as depreciation costs of the equipment, the costs to store the products, administrative salaries, and non-production equipment for back-office staff.

A note on facilities costs: This part is tricky and requires an experienced accountant to accurately assign each product. These costs need to be divided strategically among all the products being manufactured and warehoused and are usually calculated on an annual basis.

Beginning inventory and cost of purchases

It’s important to keep track of all your inventory at the start and end of each year. Your inventory doesn’t simply include the finished products in stock and ready for resale, but also includes all the raw materials you have, any items that have been started but not completed, and other supplies.

For accounting and reporting purposes, it’s imperative that both your beginning inventory and your ending inventory (from the previous fiscal year) match up exactly—otherwise, a detailed explanation needs to be included.

Further, whatever items and inventory are purchased throughout the year that don’t fall under the beginning or ending inventory must be accounted for as well. These are the cost of purchases and include all items, shipments, manufacturing, etc. As with your personal taxes, you need to keep all paperwork to show these items were purchased during the correct fiscal year.

Ending inventory

At the end of the fiscal year, it’s important to take stock (no pun intended) of all the inventory that remains. This means all products that remain and have not been sold. As we’ve discussed, this information will be used in the current COGS calculation, but will also be required for the following year’s calculations as well.

FURTHER READING: Learn how to make year-end inventory counts a little less painful.

All inventory can be categorized in resale ready, damaged (requires the estimated value of the items damaged), worthless products (evidence of destruction must be provided), and obsolete items (evidence of the devaluation). For the latter, these products can be donated to charities for a little extra goodwill.

Calculating COGS

Now comes the easy part: The math.

[ Beginning inventory + Cost of purchases + Cost of labor + Cost of materials + Other costs ] – [ Ending inventory ]

These calculations become much easier in spreadsheets or accounting software.

Moving forward with your cost of goods sold formula

As a final thought, remember that you can only include COGS if you’ve sold products. Without sales, you cannot deduct these line items. And it’s important to keep detailed accounting records of all sales and expenses in order to accurately calculate the COGS. This will also help newer businesses evaluate efficiencies and potential cost savings down the road. Remember, the ultimate goal of every business is to be a healthy profit.

Happy selling!