In the first two articles in this series, we looked at the fundamental issues affecting physical retail locations and set out the principles that could underpin a retail infrastructure where online and offline complement each other.

In this article, we turn our attention to one of the major areas where businesses are now being forced to adapt quickly by media, public and government pressure: reducing the environmental impact of modern business practices.

UK high streets are experiencing a period of rapid change and solutions tend to propose reducing the proportion of physical space available to retail and refocusing it on leisure and entertainment. As we’ve argued in this series, an alternative approach is to view retail stores as potentially vital pieces of infrastructure. The potential exists for utilising physical retail space to be something that is fully and exclusively attuned to the digital age, while also solving some of the problems inherent to online retail – bringing inventory closer to the customer and reducing the environmental impact through greater consolidation of orders.

This does require a shift in mindset, but the pressure to improve environmental efficiency has built rapidly over the past year or so – and is not likely to go away any time soon.

Volume growth

There won’t be many sectors that can ignore this growing pressure but online retail, while still technically a relatively young industry, finds itself particularly open to criticism for three main reasons – packaging waste, emissions from fulfilment vehicles, and the sustainability and re-usability of products.

In this respect, online retail is a victim of its own success. If order volumes were negligible it wouldn’t attract so much focus, but growth remains double-digit and ever building on a larger base.

What this all means is that there are large – and rapidly-growing – volumes of parcels being distributed around the UK. By our estimations, we expect 1.5 billion parcels to be dispatched by UK retailers through UK carrier networks by the end of 2018. And if that sounds like a lot, note that it excludes returns, marketplace and retailer-fulfilled (i.e. not using a third-party carrier) in-store click and collect. When these are factored in, the estimate rises to approaching 2.5 billion parcels that will be generated by ecommerce.

To compound matters, the potential for consolidation of orders – to reduce overall vehicle journeys – is being restricted by the move toward ever-faster delivery (in September 2018, 55 per cent of UK-delivered orders used next-day as the fulfilment option). Shoppers are being promised that they can receive their order quickly and at their own convenience, which shapes their expectations over time.

External pressures

The question of to how overcome these issues is complicated, but one that is gathering pace in the public consciousness due to quantifying studies being published by various sources, such as the Ellen MacArthur foundation – who estimate that waste by the fashion industry generates greenhouse emissions of 1.2 billion tonnes per year (which is greater than international flights and shipping combined, apparently).

READ MORE:

It’s an issue that the retail industry is being forced to have a greater focus on, in no small part due to the impact of the Blue Planet II series, where a stronger public awareness of the problem of plastic waste in oceans led many large brands to sign up to the Plastics Pact, under pressure from shifting customer sentiment.

How sustainable is it, in the long-term, to continually move ever-larger volumes of parcels around, largely unconsolidated, with faster delivery lead-times? It might be technically feasible, but media – and by extension, customers – will apply pressure for industry to lessen the perceived environmental impact.

A matter of perception

It’s important to note that it is complex to get an overall picture of the environmental impact of online shopping. While it does contribute additional delivery vans on the road, there is an argument that suggests this is offset by the reduced need for people to drive to the shops. RAC Foundation research in 2017 estimated that around 10 per cent of vans on the road are engaged in parcel and packet delivery, although for overall traffic this only represents around 1.5 per cent of all road transport movements in London. But this will grow in line with increasing order volumes and the move toward faster deliveries may increase its rate of penetration.

So just how culpable online retail is for emissions and unclean air in cities is a moot point. Whatever the answer is, focusing on consolidating orders to maximise efficiency over speed of delivery would ultimately be beneficial from an environmental perspective, but also reduce costs from failed deliveries and returns (as discussed in article II of this series).

Again, it’s worth bearing in mind that, irrespective of any accurate, reliable analysis of online retail’s net contribution to emissions, there is a negative perception among media and, therefore, the public in relation to it which brings pressure to address it.

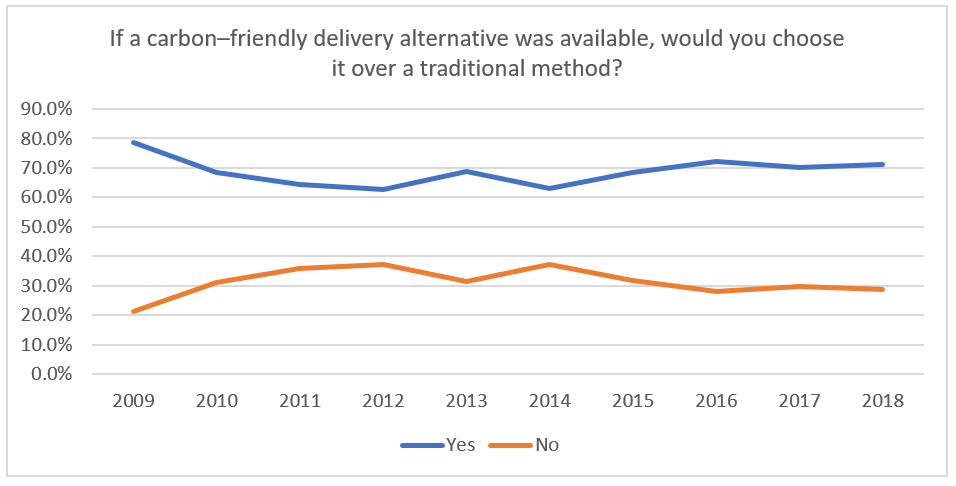

See, for example, how consistently respondents to an annual IMRG delivery survey say they would opt for carbon–friendly delivery alternatives over traditional forms, if they were available:

Distribution contributes significantly to the UK’s carbon footprint. If a carbon–friendly delivery alternative was available, would you choose it over a traditional method?

Distribution contributes significantly to the UK’s carbon footprint. If a carbon–friendly delivery alternative was available, would you choose it over a traditional method?

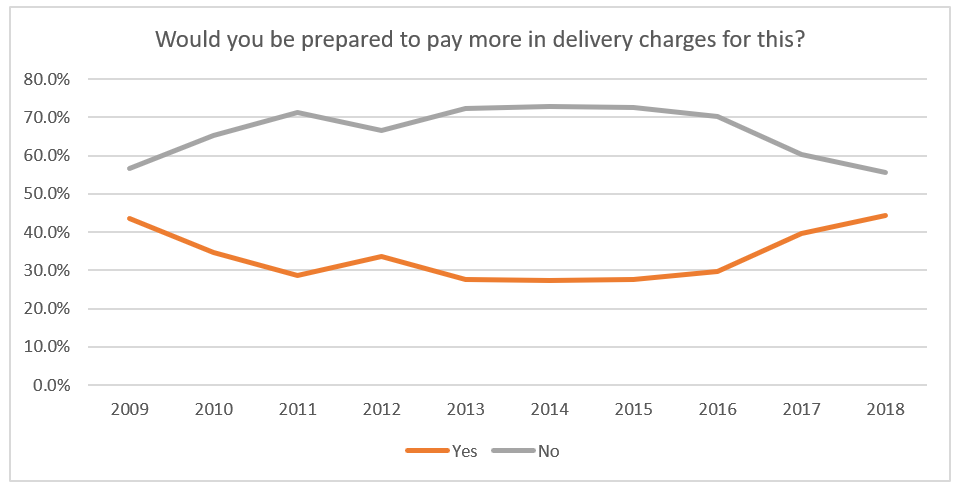

This doesn’t necessarily mean that people are willing to pay for it. The majority still expect industry to solve it without them having to pay a premium. But, as the following graph shows, this balance has been undergoing a shift over the past two years with a higher proportion saying they would be willing to pay a little more in delivery charges for environmental alternatives.

As with the momentum the Blue Planet II series created, the real pressure is around easing the more visual elements of waste, to which online shopping does contribute notably. Last year, a coalition of charities estimated that 114,000 tonnes of plastic and 300,000 tonnes of card packaging would not be recycled over Christmas 2017. Sending large volumes of orders backward and forward is a clear factor in that.

As with the momentum the Blue Planet II series created, the real pressure is around easing the more visual elements of waste, to which online shopping does contribute notably. Last year, a coalition of charities estimated that 114,000 tonnes of plastic and 300,000 tonnes of card packaging would not be recycled over Christmas 2017. Sending large volumes of orders backward and forward is a clear factor in that.

The problem with fast and free delivery

Online delivery in the UK has become a lot faster in recent years. There has been far greater promotion of next-day services (supported by later order cut-off times and checkout basket thresholds to qualify for free delivery) and same-day is offered by a small number of very large retailers.

This puts pressure on all retailers to fulfil orders quickly, with home delivery still the most popular method (for nearly 80 per cent of people) meaning that vans have to drive to different destinations to deliver the orders – and a greater likelihood for single parcels in cases where multiple orders are placed at the same time, or orders being packed into more boxes for separate delivery. If vans were able to drop off larger volumes of orders to a smaller number of locations, it would provide opportunities to boost both environmental and operational efficiency for businesses. Continuing to expand fast, unconsolidated delivery volumes in response to sporadic customer ordering patterns is likely to be the exact reverse.

In addition, each parcel has its cost. According to iForce, the average charges paid by UK retailers for the delivery of parcels is £2.87 (Q1 2018 data) and a portion of shoppers miss receipt of their delivery (the rolling 12-month average from December 2017 – November 2018, for example, shows 2.7 per cent of attempted deliveries were carded, while 11.2 per cent were not delivered on-time). The overall cost of failed first-time, on-time, every-time delivery was estimated to be almost £1.6 billion in 2018.

When “fast” applies at great scale, it’s operationally inefficient from an environmental perspective – and “free” is never actually free as far as the retailer is concerned.

Establishing guidelines around what qualifies for “fast and free”

As set out in article II of this series, incentivising customers to collect their orders rather than having them delivered to their homes has potential for improving business efficiency. though it does require high streets to become more engaging as well as cost-effective and easy to access so visiting them regularly is a more attractive prospect. As discussed above, it could also help to ease the environmental impact of online (from emissions, packaging waste, etc) through a focus on consolidation of orders and less intense demand for delivery vehicle usage.

There are no absolutes in online retail – but it should be possible to set out guidelines around which product categories or contexts may still require very fast (i.e. same-day, maybe one-hour) unconsolidated delivery, which need to be fulfilled to home and which can be fulfilled through slower, more consolidated and sustainable ways; usually involving the customer collecting it from a central location.

Technology and solutions have introduced the idea to the shopper that they can have anything they want fulfilled quickly and at their own convenience (sometimes for free, too). But – this approach is not consistent with the growing pressure around environmental sustainability and, if we think about it logically, isn’t essential either. The same level of urgency or time-sensitivities don’t apply to every product; here are some instances for when the various options may be required to illustrate this point:

- Fast / time-sensitive and home required – where the item delivered is perishable or needs to be stored in a certain way (chilled food, flowers)

- Home required but not fast – where the item is bulky and difficult to carry (beds, TVs, sofas)

In most other instances, the customer can be incentivised to collect at a place of convenience (see article two of this series for how this network could be structured). An important exception would relate to context. In many cases, if someone orders a pair of trousers it is not essential that they arrive within an hour or to home. Indeed with clothing, collection from a location that offers changing facilities is the more efficient option if the item doesn’t fit as it removes the need to facilitate a remote, unconsolidated return. But in a situation where someone is going to an important function that evening and realises the zip on their suit trousers is broken, quick delivery of a replacement – even though it is less environmentally-efficient – becomes more necessary and justified.

As technology in retail (and indeed many other sectors) makes it increasingly possible to understand individual context far better, it is that principle that could form an important determiner for which orders are appropriate for fast or slow fulfilment, that is collected or received.

CONCLUSION TO SERIES

In this series we have sought to put forward an alternative view of future physical retail space than that which often finds expression in the public domain, arguing that physical retail can (and, probably should) play a highly important role in support of modern, digital retail. There are a range of ways in which this could be enabled, with the resulting shift in shopping culture bringing opportunities for reducing retail’s environmental footprint.

As things are changing to such an extent and at such scale, the existing infrastructure is being exposed. Online retail can bring the world’s inventory to every shopper, but it has its limitations and disadvantages – as people can’t try before they buy, returns are more prominent; orders are distributed far and wide rather than in a consolidated manner; it requires a heavy final-mile presence in terms of vehicles.

To reiterate a fundamental point in all this – modern retail, for all the glitz and glamour that may characterise the marketing of brands and products, is actually just a process of connecting person to thing in the supply chain.

But trying to do this in an unconsolidated way, based around an infrastructure of single-retail-brand physical stores, will prevent physical retail space from remaining relevant to modern customer experiences; the future of the high street has to be every retailer and every product on every high street.

As with traditional pubs, there will always be some level of interest and demand for traditional stores; some will be able to keep trading profitably more or less as they are structured now. 2018 has shown us however, that it’s not likely to be the norm for all.

More radical change should be, if not embraced, at least debated.

Andy Mulcahy is Strategy and Insight Director and IMRG and Andrew Starkey is Head of e-Logistics at IMRG.

Click here to sign up to Retail Gazette‘s free daily email newsletter