George Floyd’s death at the hands of the Minneapolis police sparked outrage and protests across America that have expanded around the globe. Galvanized by a civil rights violation so egregious, citizens shaken out of months of quarantine dormancy have taken to the streets in all 50 states to demand justice. Their efforts were met with instances of police brutality, inflammatory tweets from President Trump, and more than 9,300 arrests across the country. There is no arguing that the events of the past week mark an inflection point. Instagram went dark with a #BlackoutTuesday moratorium interrupted only by reminders to vote in the day’s nine primaries.

Black designers and business leaders have been vocal about ending racial injustice. Pyer Moss’s Kerby Jean-Raymond, Balmain’s Olivier Rousteing, Telfar Clemens, and Rihanna have all made social media posts or released statements in solidarity with protestors. Rihanna suspended salesat all three of her fashion and beauty brands Tuesday in tandem with the online blackout. Jide Zeitlin, the Nigerian-American CEO of Tapestry, the parent company of Coach, Kate Spade, and Stuart Weitzman, has emphasized the company’s commitment to Black Lives Matter,stating that Tapestry would be taking further steps shortly. Appearing on Good Morning America yesterday, he elaborated on how personal these issues are for him. “From where I sit, I believe so fervently in the ideal that is America, the ideal that it’s about equal opportunity and the social mobility that comes with that. When I see the young black male that is protesting, I sit there and I think, that’s me. He’s crying out for opportunity…if he’s able to achieve the American dream, it makes all of us better.”

Examples of allyship are harder to find, even as fashion has become inextricably linked with the protests. Several marches have been followed by high-profile incidents of looting with luxury brands as targets. It should be noted that looters and protestors are rarely the same people. As sociologist Dana Fisher recently outlined in Olga Khazan’s piece for The Atlantic, these gatherings draw people with differing motivations. But the optics are the same regardless of who caused the damage. In Beverly Hills, Alexander McQueen’s Rodeo Drive flagship windows were shattered and tagged with phrases like “Make America Pay.” New York’s SoHo neighborhood, home to boutiques like Gucci, Chanel, and Coach, reported multiple storefronts defaced or broken into; similar events occurred in Atlanta, Boston, Philadelphia, and other cities. Of course, the costs associated with property damage and lost merchandise are undeniable, but the impact of these losses pales when compared to the realities of racially driven violence in America. Since 2019, 1,099 people have lost their lives at the hands of police, with black people representing 24% of those killed. The percentage is staggering when you consider that black Americans only make up 13% of the total population.

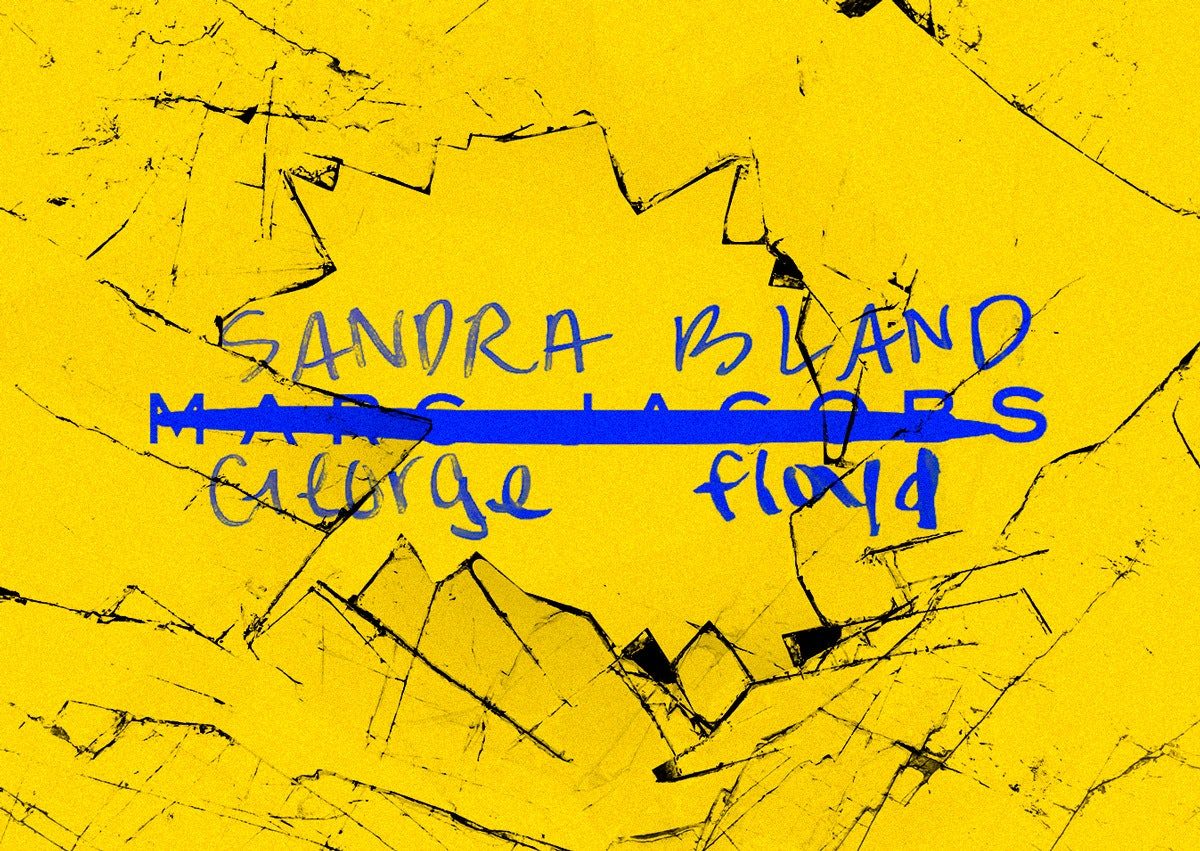

Some have taken to the internet to decry looters for the damage caused, but their statements miss the point. When a protester scratches out the name Marc Jacobs and replaces it with Sandra Bland, it is commentary about what we’ve chosen to value, and it is wise to examine why high fashion is being singled out. Responding to the damage to his New York and L.A. stores, Marc Jacobs posted a much-regrammed quote about the looting. “Never let them convince you that breaking glass or property is violence,” it read. “Hunger is violence; homelessness is violence; war is violence. Property can be replaced; human lives cannot.” Jacobs then opened things up to his followers, asking them how he could contribute and which organizations he ought to be supporting through donations. Still, as purveyors of goods that lean aspirational (read: inaccessible for the majority of the population), high-end designers and brands have become avatars of inequality.

Just as our shared experience of the coronavirus pandemic caused many to rethink our relationship to the products we purchase, the epidemic of police brutality and racism will alter the way we consume. The anger surrounding these issues has led a small minority to ransack stores in acts of desperation and rage, but these are temporary problems. The real danger will come when consumers undertake a mass reassessment of the brands they support and invest in. When the dust settles, who will people side with: the companies that were vocal in their support, or the ones who were complicit through silence?

The past decade has seen an uptick in brands that market themselves via their use of terms like “inclusivity”, “diversity”, and “acceptance”, latching onto broader social movements to prove themselves woke and/or connect with millennial and Gen-Z consumers. The moves can come from a place of genuine concern—corporations aren’t people, but the humans behind them often use their platforms to promote causes close to their hearts. Brands’ silence in the face of the current crisis calls that kind of sincerity into question. Without minorities on creative teams and in executive roles, the social media gestures are empty—especially when issues pertinent to their communities are ignored. Any company that values the $1.2 trillion force that is black buying power needs also to value the safety of black citizens.

During the crisis, many within fashion have been confused about what they should be doingand how best to approach the situation. While no gesture will please every single person, there are existing initiatives in need of support. The 15 Percent Pledge launched by Brother Vellies designer Aurora James calls for influential stores like Net-a-Porter, Saks Fifth Avenue, and Sephora to source 15% of their products from black-owned businesses, a move that would illustrate a commitment to long-term change. Magazines and websites, Vogue included, could undertake a similar agreement, dedicating pages and site space to creatives of color and their work.

Fostering talent through grants, funds, and scholarships is also needed. Even internships—the first step for many when they enter the fashion business—could use a revision. If unpaid labor is the sole way to get your foot in the door, only a select few can get the experience necessary to advance. Implementing paid programs that allow interested students to earn while shadowing a mentor is one way to help level the playing field. Likewise, efforts to assist creators already in the industry must be redoubled. This month Harlem Fashion Row launched a nonprofit, Icon360, to raise funds for designers of color impacted by the coronavirus shutdown. The virtual fashion experience, which featured Q&As with the photographer Tamu McPherson and the stylist Mobolaji Dawodu, gave 100% of its proceeds to help black brands through a period of financial uncertainty. Though the organization was created in response to a separate issue, it is precisely the kind of project that corporations should support with the signal boost that comes with leveraging their network.

Brands can also foster collaboration with black artists and artisans, putting their creativity and names at the forefront of collections instead of engaging in the appropriation that still permeates our runways. Behind the scenes, black voices must be amplified to a place where they are present in and integral to the decision-making process. In the book-publishing industry, sensitivity readers have become the norm, screening novels before release to assure that their depiction of non-white characters is respectful and informed by reality. Fashion could use similar checks and balances; how many gaffes have occurred over the years involving items that have disrespected people of color? Those instances need to be prevented, not excused via apologies. Gucci’s appointment of Renée Tirado as its head of diversity and inclusion last year was a step in the right direction; similar positions should exist within every house.

There should never again be a time when there is only one black designer at a prominent house, one black CEO helming a corporation, or one black editor of note. For those individuals, the solitude of achievement is isolating, but for the greater community such tokenism is ultimately harmful. The idea that there is only room at the top for one black person is steeped in “magical negro” stereotypes and destructive ideology. No individual can encapsulate the richness of the black experience or that of any minority group, for that matter. A community of millions will never be a monolith. Brands should be open to the idea that their boardrooms, editorial, and creative teams need to be as diverse as their advertising campaigns if they are to engage with the multitude of cultures and viewpoints that comprise blackness.

Financial contributions have never been more valuable, especially when they come with a message of unity. Over the weekend, beauty innovator Glossier updated its social media with the news that it would be donating $500,000 to organizations combating racial injustice, the NAACP Legal Defense, Black Lives Matter, and the Marsha P. Johnson Institute among them, plus a matching contribution to a grant for black-owned business. By acknowledging America’s unrest and making a definitive statement against racism, Glossier did more than most.

Not every brand has a million dollars to devote to supporting activism, but every brand has a platform. The movement needs leaders, advocates willing to forget what was taken, and focus on what can be gained. Beyond making statements online, fashion must move to evolve its hiring practices, brand messaging, and commitment to causes, even if they risk alienating some consumers. It will take humility to broach these topics and to invest in long-term advocacy; the path forward will not be easy, but it is necessary. It’s telling that the most appropriate response to the week’s events came from the musician and Golf Wang founder Tyler the Creator, who was among the thousands to march in Los Angeles on Sunday. When his Fairfax Avenue store was vandalized during the protests, he responded with a nod to history. Beneath a photo of members of the Black Panther Party in 1969, he wrote: “The store is fine, but even if it wasn’t, this is bigger than getting some gas fixed and buffing spray paint off. Understand what really needs to be fixed out here.”