Taking to the open road is a summer ritual for millions, but a new joint exhibition in Newport, R.I., considers how that impacted fashion, women’s role in society and fashion’s impact on the automobile.

“Women Take the Wheel: Fashion, Modernity and the Automobile 1905-1945” is being showcased at the Audrain Automobile Museum and “The World in Motion: Vanderbilt Style” is on view at the Newport Historical Society through Aug. 22. More than century-old clothes and vintage vehicles, the two-part show encapsulates how women driving and being driven affected the way they dress. It also touches upon American consumerism in the First World War and how women entering the workforce shifted society and led to independence on and off the road.

The exhibition at the Audrain showcases a 1902 Packard Model F, an open-carriage vehicle that marked the move from earlier horseless carriages. Donald Osborne, chief executive officer of Audrain Automobile Museum & Collections, said, “The automobile absolutely helped to liberate women from some of the constructions of the time. You can also see the automobiling was an adventure so what you might wear for a formal luncheon was not appropriate to go out for a ride in your automobile.”

The show zeroes in on the early 20th century when American women became more social, due partially to working, sporting activities and driving for travel and for pleasure. Ten automobiles from the early 1900s to 1945 are also on view. As fashion adapted accordingly, Newport and the automobile were integral to this shift. Visitors may be most surprised to learn about “just how much of a connection there was between fashion and automobile design. There are really connections about the line, the silhouette and decoration,” said Rebecca Kelly, visiting scholar of fashion history at the Newport Historical Society.

The fashion and the roadsters of Newport’s heyday are coming together in another way. “Downton Abbey” creator Julian Fellowes is filming the “Gilded Age” series for HBO in Newport. Having seen the filming around town, Kelly said, “it’s a wonderful overlap of circumstances that this really high-profile production is right here in town and we are dealing with the real Gilded Age, where they’re recreating it — so it’s really fun.”

Instead of driving between the museum on Bellevue Avenue and the nearby historical society’s Touro Street location, exhibition-goers are encouraged to stroll along Bellevue Avenue to eye many of Newport’s historic mansions, including The Breakers, the 70-room manse that railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt built. Built between the 1850s and 1900, Rose Cliff, Marble House, The Elms, Rough Point and the other mansions were initially known as “cottages,” and several remain in their Gilded Age splendor, as visitors and movie fans can attest.

Dresses, accessories and garments previously worn by Alice Vanderbilt and two of her seven children, Gertrude and Gladys, are on view at the museum. When her husband, Cornelius Vanderbilt 2nd, died in 1899, his estate was appraised at nearly $73 million or had a net worth equal to $2.27 billion based on 2020 dollars. “One of the things that really impresses me so much about Newport, and one of the reasons why I am here in this job and living in this city, is the way it lives its history everyday. We make our lives on these streets that people have lived on and made their lives on since 1639,” Osborne said.

Newport played a leading role in the international lifestyle in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as evidenced by the resort attire on display. One of the draws of the exhibition is how Alice Vanderbilt’s lengthy life — she was born in 1845 and died in 1934 — chronicles the dramatic changes that shifted women’s fashion. In the early days of her marriage, for example, she probably changed five times a day, starting with an ensemble for the morning, another for the afternoon, something for a carriage ride or promenading, perhaps an afternoon tea and then another change for dinner. Decades later “all that prescribed Gilded Age etiquette started to ebb away. She really started embracing American sportswear that was much more simple in the types of fabrics and silhouettes,” Kelly said.

Along with a 1908 Packard Model Thirty gentleman’s roadster, a 1911 Rauch & Lang electric roadster and other cars, there will will be 40 pieces of dresses, shoes and accessories dating between 1893 and 1945. Most of the garments belonged to the three Vanderbilt women, who divided their time between Newport and New York. A trio of designs that Alice Vanderbilt bought at Maison Paquin, Jean Paquin’s couture house, in 1913 will be among the highlights. In addition to items from the Vanderbilt family, there will be coats, driving goggles and hats from the historical society’s collection. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who was a sculptor and later founded what is now known as the Whitney Museum of American Art, favored the decadent fashions of the 1910s such as a 1915 silk-cut evening coat by Mollie O’Hara that is on view. Gladys Moore Vanderbilt, who married into diplomacy and was known as Countess Szechenyi, favored looks from Hattie Carnegie, some of which are on view. With five children and philanthropic pursuits, her wardrobe from the 1920s and ’30s also featured pieces from Budapest-based designer Julia Fischer.

Fashion and a car that once belonged to longtime Newport summer resident Doris Duke will be on view. A 1938 Packard Twelve Landaulet that the American Tobacco Company heiress and socialite once wheeled around in is on loan from the Newport Restoration Foundation that she largely funded in 1968 and which helped to save 80 historic buildings.

Sightseeing, picnicking and beach going allowed for a new kind of freedom for the more affluent members of society. The Vanderbilts were of that camp and had been accustomed to the sport of coaching, better known as carriage driving. Familiar as they were with coachmen and later chauffeurs, the younger kin liked to drive themselves. They also alternated between horses and horseless carriages. The press caught up with Gladys Vanderbilt, for example, in 1905 behind the wheel of a new Mercedes motor car at one point, and commandeering her open-top road coach at another.

All that open-road driving on unpaved dusty roads could take a toll on drivers’ and passengers’ appearances. Lightweight coats called “dusters” caught on for their practicality. Hooded versions, veiled hats, driving masks, goggles and gloves offered extra coverage and polished off the look.

One of the hooks that brought the car museum and the Newport Historical Society together was the fact that one of Alice Vanderbilt’s favorite New York City designers, Mollie O’Hara, had a summer outpost in the historic Audrain Building, which is now home to the automobile museum. Her summer pop-up, so to speak, was there from 1908 until 1929 and gallery space has been used to replicate what her early-20th-century shop in Newport looked like.

For much of its history, the Audrain Building housed high-end retailers including Brooks Brothers, which had a shop during part of the time that O’Hara was there. “A lot of the dressmakers, who rented space here, really did it as pop-up shops. They came each summer. It was really exciting along the avenue [Bellevue] as the summer season got underway. A lot of the luxury purveyors from New York followed them on their summer vacation,” Kelly said, adding that archival information details how Alice Vanderbilt ordered some dresses from O’Hara’s Fifth Avenue location and picked them up a few weeks later in the New York store. True to the transitory moment in fashion that O’Hara represented in combining custom work and retail, she had a selling room in the Audrain Building.

All that seaside seamstressing paid off for O’Hara, who became a longtime summer resident in Newport, thanks to her strong business. “At the time of her death [in 1941] she was definitely a millionaire,” Kelly said. “Mollie had a lot of neighbors and competitors. There was this whole group of New York luxury retailers. They were competing for storefront space and they didn’t always wind up in the same exact spot.”

Having previously spent more than a decade working in retail and product development at Macy’s and Brooks Brothers as well as an uptown men’s wear store in Manhattan, Osborne said. “One of the things I love most about automobiles is the way that fashion and automobiles represent the culture. They are sociologically so entwined and important. Probably 80 percent of what women wore in the 1880s was completely inappropriate in a motor vehicle by 1905 — and certainly 60 percent of what men wore was. The coming of the automobile had a profound effect on fashion. It was probably a more profound effect than any other technological advancement that man had ever seen before. Perhaps central heating had an equal effect on clothing but the automobile certainly had the most dramatic and immediate effect on fashion.

“Fashion helped shape the automobile. Something that was looked on as a functional object at its creation, albeit for the very wealthy, soon became something that was very commonplace. People wanted to look for areas of diversification and personalization. Fashion was something that no one would really speak about when it came to the motor vehicle period immediately following WWI, when it was commodotized with the Model T and all that. But very quickly by the mid-1920s, fashion with its styling, colors, patterns and design became very important with the automobile. It was a very much a two-way street,” Osborne said.

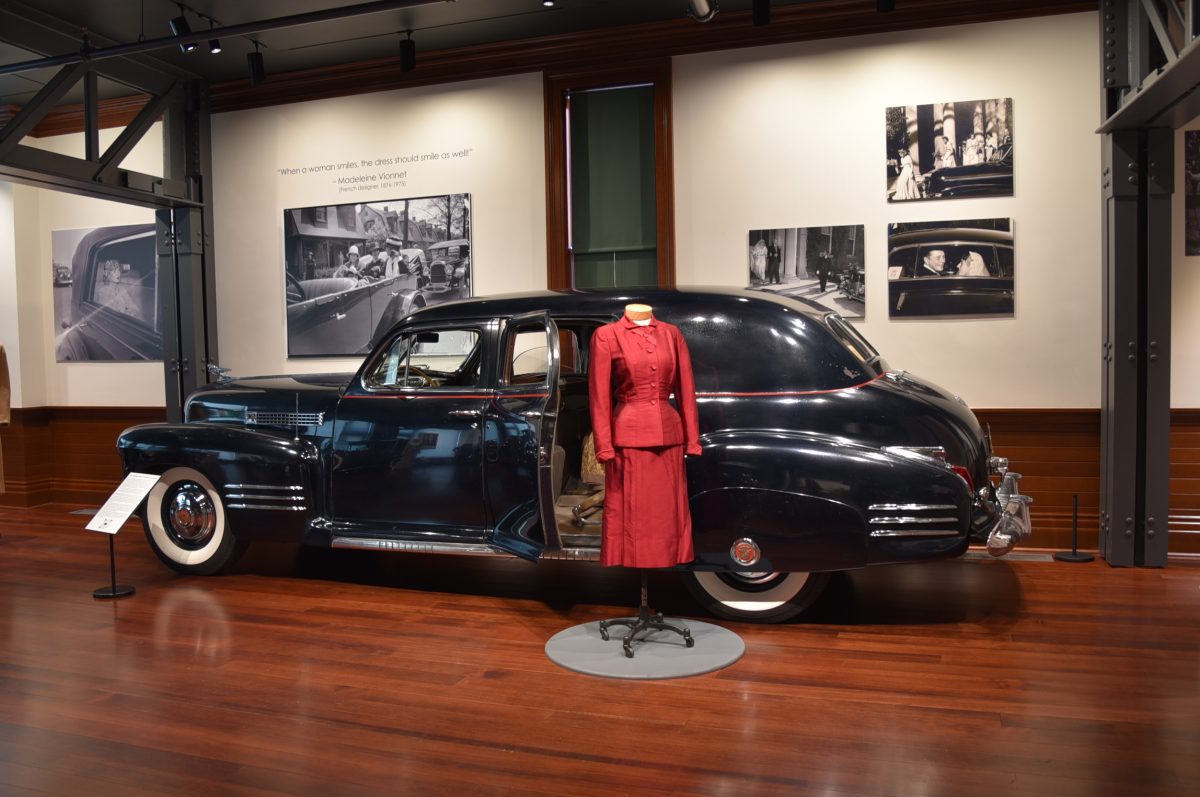

As visitors can see from the period photographs in the exhibition, passengers and drivers dressed flamboyantly since they were very much “on display in an early car,” Osborne said, adding that the chassis with their rudimentary bodies had chairs high above the road. That explains the big hats. During the course of the exhibition, which ends with a 1941 Cadillac limousine and fashion of 1945, the mood shifts from one of display and open-showing to very much concealing and quiet, Osborne said. By the ’30s, cars were increasingly designed to conceal passengers. “It’s also a very interesting sociological comment, too, about what wealth means and display means,” Osborne said.

Having written “Transatlantico/Transatlantic Style: A Romance of Fins and Chrome,” a book about the creative exchange between Italy and America in automotive design in the decade after WWII, Osborne said. “The whole idea of cross influences in design and in culture is an important part of this exhibition.”